The last few days, I was busy with 2 events in a row. From last Thursday to last Saturday, as a partner of CF40, China’s leading economic think tank, I attended their annual Bund Summit. CF40’s new Substack, which my team helps manage, will soon share some key takeaways and snippets from this year’s Bund Summit.

Immediately after the Bund Summit, we started Baiguan’s first China tour, bringing more than a dozen investors and business leaders from Asia, US and Europe through a 4-day tour of large and small Chinese companies in consumer and deep tech industries, meeting with local founders and senior managers. Our team will share many of our takeaways from this tour next week in the Baiguan newsletter.

The participants in the China tour are impressed by various kinds of progress that Chinese companies have been making, but they are not without concerns. One prominent question touched on an especially binary risk. A European investor, badly burned by the Russian experience, asked several times during the trip: Can and will the US shut China off the US dollar system? How can we prepare for such a risk?

In fact, at this year’s Bund Summit, one prominent economist also asked exactly the same question during a VIP session, and he provided quite a convincing answer.

I will not name him but refer to him simply as the Economist here, and I will summarize his key logic for you in this essay.

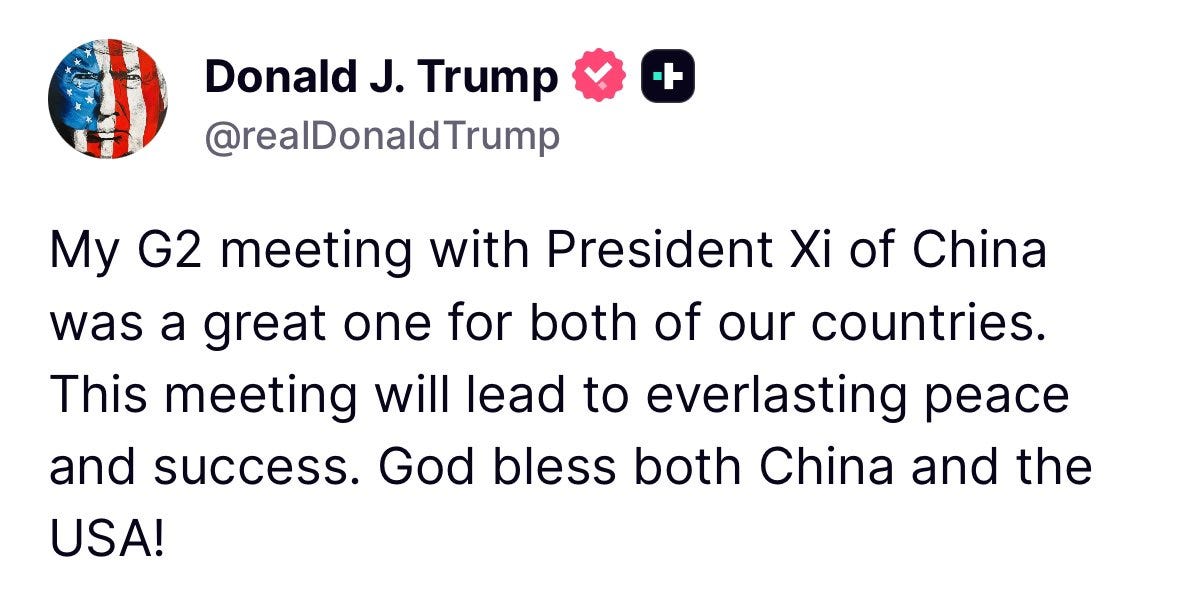

While I was busy meeting people, big meetings were taking place on the world stage. Top trade officials from the US and China (which, of course, included Mr. Li Chenggang) met in Kuala Lumpur, followed by the much-anticipated meeting between Xi and Trump in Busan, South Korea.

By now, it’s safe to say that the 7-month-long US-China trade war has come to a full pause. Both sides have shown their cards. And although it’s debatable if China has emerged as a victor, there is no doubt that the US is the loser, so much so that I find myself strangely agreeing with Rush Doshi, someone I normally would not agree with on virtually anything else.

Tariff

On the tariff front, China stood her ground. Not only did the 100% tariff hike threatened by Trump evaporate almost immediately after it was announced, but China also had a 10% further reduction in the “fentanyl tariff”. With a combined tariff rate of around 47%, China’s exports to the US are now as competitive as those of other parts of the world, and in some cases even more competitive, such as when compared with India and Brazil.

What’s more important is that half a year of these US tariffs hasn’t meaningfully hurt China’s exports at all. Why? The Economist believed that the key reason is that, in the seven years since the first trade war, China’s businesses have already built up a sophisticated global supply chain. This is not about transhipment, but genuine production and assembly in third-party countries, utilizing upstream materials and components sourced from China.

The Economist pointed out that the US wants 3 impossible things at the same time: high growth, low inflation and reducing trade deficit. If the US wants high growth while reducing trade deficit, there will be high inflation. If the US wants low inflation while reducing trade deficit, some kind of recession must happen.

Since growth and inflation are more important, the US has to make sacrifices on the trade deficit, at least for now. This ensures that, according to the Economist, there will always be TACO.

Export control

Another important aspect of trade wars is the export control on key supply chains. Here, the tables have completely turned. After the Kuala Lumpur-Busan talks, the US agreed to delay the so-called “BIS 50% rule” by one year, in exchange for China to delay the implementation of its rare earth export control as well.

October marked the first time China played the rare earth card against the US. And China has played this well. No longer is it a one-sided battle with only China suffering. Now, for the first time, the US has also realized that it could also be vulnerable.

The US and China now have a stranglehold on each other, but the pains are asymmetrical. For China, the expectation of restrictions on its technology has persisted for at least seven years. However, the US has only just begun to realize it. However, at least a few years will pass from realizing the problem to solving it. And by that time, China will hopefully have made significant progress as well.

What’s aiding this asymmetry is that China now apparently doesn’t seem keen on purchasing Nvidia’s high-end chips, showing preparedness and determination to finally break free.

All of this asymmetry, according to the Economist, ensures that US tech export control will not be an effective weapon in the near future.

Financial sanctions?

Given that both tariff and export control measures have been defanged from the US, it is just natural that the imagery and wording from the Busan meeting marked the first time China has been recognised by its counterparty as a real peer.

But what about the financial sanctions? The Economist believes that this is the only important weapon left in the US arsenal. So far, the US side has refrained from using it. But will it ever use it?