Two prominent online influencers in China, Hu Chenfeng户晨风 and Zhang Xuefeng张雪峰 have been silenced by censorship, stirring widespread speculation about the policy motives behind.

It’s not known whether this is a permanent ban, but as of today, on China’s social media platforms, you won’t be able to find their own accounts. (You can still find many of their video contents shared by third-party accounts, suggesting that the ban is a punishment to deprive them of user attention and income streams, rather than a blanket obliteration of memories about them. This implies that they have not crossed the most extreme type of red lines, and that whatever their wrongdoings are not criminal.)

These two influencers have no relations with each other, and they specialize in distinct kinds of content. But the fact that they have been banished around the same time deserves attention.

Among the two, Hu is younger and has been famous more recently. Coming from a humble background, he first made a name for himself by conducting interviews with grassroots individuals, investigating common livelihood issues, such as the purchasing power of 100 yuan in different cities and different countries. Besides shooting short videos, he was known for hosting live streaming sessions, during which he received calls from random viewers. His signature opening questions were always about education level, occupation, income level, and type of mobile phone, satisfying the voyeuristic desires of his audience.

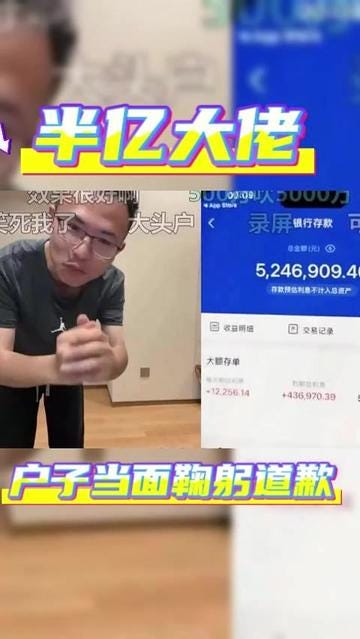

Increasingly, he became more and more obsequious to the rich. For example, in one show, he received a call during his livestream. The guest claimed to have 50 million yuan (~$7.5m) of assets. Hu “ordered” the guest to open the camera to show his home, and after seeing his humble kitchen, Hu scolded the guest for lying. But after the guest showed his bank balance stands at over 5 million yuan, Hu stood up, bowed repeatedly, and apologized dramatically.

The pinnacle of this obsequiousness to the rich was the “Apple person vs Android person” theory that he created, which many people assumed led to his ultimate downfall. “Apple” is Hu’s word for being rich and having good taste. It’s not just about having an Apple phone, but driving a Tesla, shopping at Sam’s Club, and living in a big apartment are all considered having an “Apple” life, while the opposite is “Android”. When someone called in with poor microphone quality, Hu called him an “Android person”, with “Android logic”.

It is true that in many people’s minds, Apple stands for the premium, while domestic phones like Xiaomi and Vivo, which mostly run on Android systems, are considered to be sub-premium. But it can still be a shocker when this is explicitly talked about and applied to all facets of life in order to categorize people into different classes.

Not long before he was banned, he received a call from one of his early followers during a livestream. The follower scolded him for betraying his roots, calling Hu's “Apple person vs. Android person” theory a disgrace, and stating that Hu would not be far from his downfall.

In comparison, Zhang Xuefeng was famous much earlier. An education consultant who helped students apply for graduate schools, he was first brought into the limelight in a viral video in 2016, where he shared a funny take on 34 of China’s top universities in 7 minutes. And he has gradually grown in popularity ever since. Before Zhang was silenced, he had already garnered over 40 million followers on Douyin.

Zhang was famous for his bombastic, unforgiving, and politically incorrect takes. In 2023, he made national headlines sharing his disdain for any humanities major, calling anyone who majors in humanities will eventually end up in the service industry and would just be “licking舔” (at their clients).

In a famous episode, he laughed at a parent whose child, with excellent STEM grades, wanted to study journalism in college to fulfill his dream. Zhang’s advice to the parent was to beat the child into a coma in order to stop him from having this silly idea. He further stated that anyone should just blindfold themselves and pick whatever random major, and it will still be better than journalism.

For many people, Zhang’s ideas are rude, and his style of delivery looks almost like a villain. However, for many others, Zhang is merely the anti-hero who reveals the unfiltered truth to common people, free from propaganda, fantasy, and lies, for their own benefit.

The direct trigger for Zhang’s banning, though, is widely believed to be a leaked video of an internal speech he gave after the recent military parade. In that video, with his usual fiery style, he proclaimed that the same day the PLA sends troops to Taiwan, he promised to instantly donate 50 million RMB. His audience, mostly his students, clapped ferociously.

The video was leaked on foreign platforms, such as X, and created a significant amount of controversy. He knew he was in trouble. A few days later, in his livestream, he was furious and wanted to find the perpetrator. Still, he shrugged off this episode and laughed that he was not afraid.

Only a few days later, he was gone.

If reunification with Taiwan is the long-stated policy of the PRC, why would Zhang be banned because of it?

First of all, as much as you should not under-estimate China’s resolve to reunify with Taiwan, you should also not under-estimate the resolve to reunify PEACEFULLY. (I plan to write about this topic one day.) At the very least, war or peace, the CPC does not like the narratives of a topic of such utmost importance to be shaped by such an unsavory demagogue, right after the Big Parade was successfully concluded. If Zhang doesn’t face consequences, what kind of message is the CPC sending to the world?

On the other hand, I also don’t think the punishment would have been so drastic had Zhang not been such a controversial figure to start with. The fact that Zhang was censored at the same time as Hu and similar KOLs suggests that it’s not just because of a single video. Rather, these cases happened directly as a consequence of a recent online campaign launched by CAC, China’s internet regulator.

On September 22, CAC announced that it would launch a two-month campaign to fight “maliciously stirring up negative emotions/issues.”

Targeted behaviors include:

Inciting extreme group antagonism. This includes exploiting social hot topics to forcibly associate them with identity, regional, or gender labels in order to stigmatize and sensationalize, thereby provoking inter-group conflict. … Certain subcultures, such as “ACG communities” or so-called “troll youth” groups, have even been found to incite hostility, engage in “doxxing,” or teach others how to buy and sell doxxing services.

Spreading panic and anxiety. This … targets fabricated or distorted details about events that feed conspiracy theories or sensationalism, as well as false personas posing as “masters” or “experts” who exploit concerns around jobs, marriage, or education to sell products or courses.

Stirring up online violence and hostility. This includes scripting or staging fights, bullying scenarios, or malicious pranks to glorify “violence against violence.” It also covers sharing raw, graphic footage of bloody or horrific scenes, or distributing disturbing images/videos involving animal abuse, self-harm, or extreme acts. …

Over-amplifying negativity and pessimism. This includes concentrated promotion of extreme or absolutist claims such as “hard work is useless” or “education is pointless.” It also covers malicious interpretations of social phenomena, exaggerating isolated negative cases, and using them as opportunities to spread nihilistic worldviews. Further, it targets the creation of so-called trending terms, memes, emoticons, or catchphrases that excessively demean oneself or glorify despair and apathy, leading to unhealthy imitation and viral spread.

It appears this new campaign is tailor-made for the likes of Hu and Zhang. Hu’s “Apple vs Android” theory, Zhang’s “Humanities is worthless”, and “I will donate 50 million RMB the moment the war breaks out in Taiwan”, can all be found here, from stigmatization of social labels, to inciting violence and hostility, to sensationalism, to glorification of no hard work and no education.

The commonality between Hu and Zhang is that both of them owed their success to tapping into social anxiety in the first place. Hu’s exposé about actual inflation levels and the realities of poor people’s lives, and Zhang’s earnest and practical advice for graduate students, all touched on the right nerves.

But as they became more and more successful, social anxiety morphed into division. “Your logic is Android”. “Let’s donate to our cause in Taiwan!”

The big backdrop for all of this is the increasingly dire youth unemployment situation. These influencers are merely channels through which these sentiments find expression, and the authorities are now afraid that negative sentiments will be self-reinforcing and lead to unbearable social tension.

Unemployment is also shaping up to be a global phenomenon, with slower growth everywhere and the rise of AI that threatens to eliminate many junior white-collar jobs. Everywhere around the world, from the US to Germany, from Italy to even Japan, the rise of the alt-right is a direct consequence of this shifting ground.

What has surprised me recently is that such alt-right sentiments are also quite palpable here in China, as showcased by the recent controversy about the “K visa”.

This will be the main subject of my next briefing.

The difference between China and the USA is that in China it's clear in everyone's mind that the government did the censorship, in the USA everyone knows that besides the government, hiding behind corporations, sometimes it's just pure greed that gives rise to censorship. Both could use some clarity, but I expect not much in either case.

If Chinese censors issued reasons for censoring (with avenues for appeal) it would make free speech more effective for engaging in reasoned discussion.