Tech, work culture, services industry, the mystic, purges, and 1989

Anniversary ask-me-anything Q&A - 2025 edition

Welcome to the 2nd anniversary Q&A at China Translated. I have received quite a number of questions, covering a wide array of questions including China’s next technological breakthrough, my reader distribution, work ethics, spirituality, social norms, China’s service industry, and also sensitive topics such as VPN usage and what happened in 1989. Because of a busy schedule I only manage to finish replying to them just now.

Before I start, I would like to remind you that a week ago I published the following article evaluating to what extent we are in an AI bubble at Robert Wu's Portfolio, a new newsletter currently at trial stage where I put ideas into investment action, and is not just limited to China. Hope you enjoy:

With that said, let’s begin the Q&A.

Q: After electric cars and solar, which next cutting-edge technologies do you expect China to take the lead on?

First thing has come to my mind is biotech. Chinese companies have demonstrated a clear advantage in biotech, which is on track to repeat the same EV experience in the next few years. It’s highly likely that 3 years from now, the world will have a full reckoning that so much innovation in drug discovery is happening in China, the same feeling that people now have about EVs. This is what Morgan Stanley has to say about this topic.

For truly unique and groundbreaking innovation, China is betting heavily on commercial nuclear fusion. This year, China has even established a new state-owned enterprise dedicated to this area. We are still far away from commercially viable nuclear fusion, but if any country in the world is able to win this holy grail, it must be China, due to its strong engineering base and the unique ability to marshal society-wide resources into strategic projects.

If China can achieve this, it will not only definitively put aside the debate about whether China can do “real innovation” but also achieve something truly historic for mankind.

Q: Which countries are your readers from? I ask because I see so much written with the American reader in mind. Even Canadians who write for a living write for an American audience. I think that is a detriment, because people read just an American perspective … How did you find Substack? Maybe you chose this because you exactly wanted to connect with American readers?

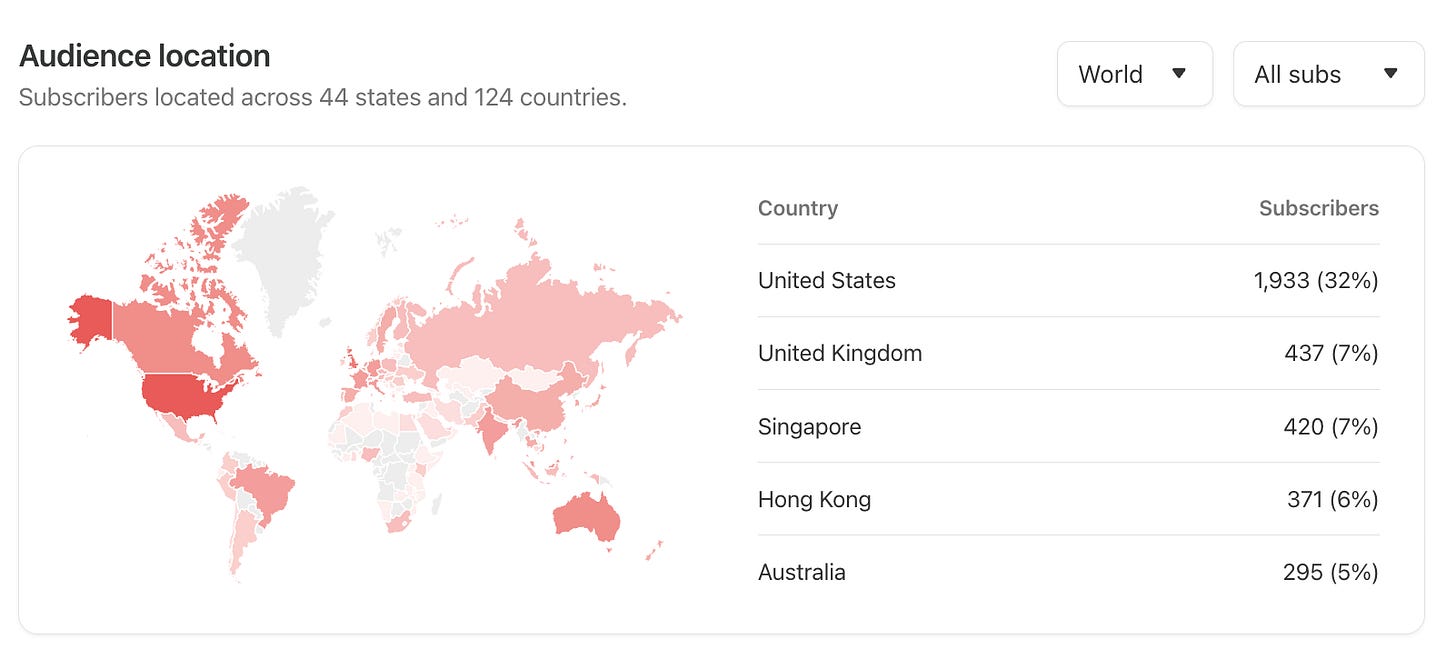

A: This is the distribution of China Translated’s readers:

It’s true that US readers make the largest bloc, at 32%. This is understandable since Substack is a US app. All English-speaking countries and territories make up ~60%. Non-Anglo Europe accounts for around 20%. There are also a sizable number of readers from India and Brazil. Overall, I believe my readership profile is quite balanced, and I don’t see myself specifically writing to an American audience.

A core reader bloc consists of overseas Chinese people, mostly second- and third-generation immigrants from Singapore, Malaysia, the US, Thailand, Indonesia, Canada, Australia, and even Mexico. I speculate that this bloc accounts for at least 20% of all readers, but they tend to be the most committed, so that they make up perhaps around 50% of paying subscribers (the same also holds true for Baiguan).

I think this totally makes sense. For the overseas Chinese community, China is familiar and strange at the same time. Similar cultural upbringing has conditioned them well to appreciate the deeper logic behind many phenomena, so China becomes a relatively easier subject for them than, say, Americans. Still, their home countries are very different from China, so they also struggle to make sense here and there. Being ethnic Chinese also makes them curious about what’s going on in China. All of these mean that they have a strong demand to understand, yet the number of trustworthy sources out there for them is not many. I suppose that’s why they have found me.

Q: What would be your take on these accounts of the dramatic Tiananmen Square events in 1989?

Ahh… This is a tough one.

Tiananmen was such a controversial event that, over the years, its life as a political symbol has continued to grow. Although I was born after that, it was also a “visceral” experience for me. The first time I learned about it also marked “the first pivot” of my political awakening, which I documented well in this article.

My overall assessment of the event has progressed from shock, to anger, to understanding, and finally to a very complicated feeling now. It’s one of those subjects that I would one day want to write about in a more fully fleshed-out way. However, before that, I highly recommend watching the documentary "The Gate of Heavenly Peace." This is the most balanced piece of work out there I have ever seen on this subject, and a must-watch for anyone who wants to form an opinion on this issue.

For my own opinions, let me just share several key takes that are less frequently talked about in the general discourses:

The events in 1989 were not limited to Beijing. Almost all of China's major cities saw large protests. Many people from my parents’ generation joined those “protests” from all over China. My mother didn’t even think it was a protest, but rather like joining a festival. So it was not just any protest. It was a nationwide mass movement that demanded an answer in one form or another.

Most people tend to overlook the fact that, at the core of this event, was a significant power struggle at the top. Just as the Cultural Revolution was a power struggle at the core, with Mao rallying the masses outside to smash his adversaries, the events in 1989 could also well turn into a palace coup with strong popular support from the outside. In fact, the power struggle aspect of the event was what kept the protests alive for more than 2 months. Protestors knew that there was indecisiveness and internal differences inside Zhongnanhai, and the protests dragged on way beyond the point where they could be resolved peacefully.

Had the protestors succeeded, it would be certain that the student leaders would join the upper echelon of China’s power structure. However, considering their demeanors during the protests, I am extremely doubtful that they can handle this well. They were college kids with lofty dreams and big ideas learned from Western books. In that regard, these students were not so different from the elders that they sought to topple, who were also once Western-inspired students as well, agitating for a revolution 70 years prior, before they themselves were hardened by decades of war and struggles. So, if these kids had their way, I don’t think they would be able to govern a vast country with a GDP per capita of only $311 at the time and a population that mostly had zero inkling of an idea of what democracy means. They would quickly lose control. In the ensuing chaos, something far worse, such as a military dictatorship, could emerge from the cracks.

I don’t deny that I am also traumatized by the human costs of that event. But if you do enough research from all sides and thinking about it, by June of that year, if things hadn’t developed in the ghastly way they eventually did, the best-case scenario I could imagine is that China would become what Russia is today. I will leave you to decide which one is more preferable. I believe you already know my answers.

Q: How does the work culture in the Chinese work environments you can speak about compare to the American work culture described in the comments section here?

A: Historically, hard work and extreme hard work are cherished. Such as the infamous “996” culture. However, in recent years, a growing backlash has emerged against this. Despite this change, I still believe Chinese people are comparatively more workaholic than most other peoples. The whole concept of “involution” wouldn’t be a subject of controversy if it ceases to exist.

Q: You wrote that “Using a VPN is illegal in China”. Would you please cite the relevant section of the criminal code and which section or article it comes under? Here’s the link to the Criminal Code in English:

A: Illegal doesn’t necessarily mean “criminal” in China. A criminal conviction can lead to imprisonment and more severe penalties. However, many illegal actions may only lead to monetary fines, and sometimes only a warning.

Using a VPN falls under that category.

You may refer to “中华人民共和国计算机信息网络国际联网管理暂行规定Interim Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on the Management of International Networking of Computer Information Networks”:

Section 6: Computer information networks that directly connect to international networks must use the international channels provided by the state public telecommunications network. No unit or individual may establish or use other channels for international networking.

Section 14 also specifies that breaching of Section 6 can lead to:

The public security organ shall order the termination of networking, issue a warning, and may concurrently impose a fine of not more than 15,000 yuan.

Q: For a good while, it used to be the case that the Chinese were more materialistic rather than idealistic or spiritual. But, the young generations tend to perceive a need for more spirituality. And, meanwhile, China proved rather outstanding in systematic studies, in sciences. My question is: How do the Chinese stand regarding scientific studies that suggest the existence of a spiritual domain? Viz., studies of Chi Gong, of ‘distance healing,’ and “near-death experiences.” Can you go to WeChat, enter a bookstore or a library, and find works on those topics? How much public interest there is for those fields?

A. The interest in the mystic is huge and has always been huge. This is always the deep undercurrent in China that few people can see and quantify exactly. You will be surprised by the number of highly educated people who are into fortune-telling. I am also quite interested in these kinds of topics, but I am approaching them more as a skeptic. You probably don’t know yet, but I have “secretly” opened a newsletter about this almost a year ago, called unbodied. So far, I have written only one essay, about one mystic experience, but you may expect me to be more serious about this newsletter, perhaps when I get older and have more free time.

Q: Mencius: “There are three things which are unfilial, and to have no posterity is the greatest of them.” (Mn. 4A.26). Among the current generations of Chinese, does failure to have descendants cause a sense of guilt? If so, in what percentage of childless people, and to what degree?

A: That sense of guilt is rapidly diminishing in contemporary China. Otherwise, we wouldn’t have such a significant drop-off in the birth rate.

Q: My impression, which could be mistaken, is that Chinese manufacturing is pretty efficient and advanced, and while not necessarily the best or most efficient in every category of manufacturing, not too far away. However, when it comes to services, my impression is that China is generally much less efficient and productive than the US. First, does that seem accurate? And secondly, if that is accurate, what’s your opinion on why productivity lags in China’s service sector?

A: It’s not a matter of efficiency, but a difference of perceived value and story-telling. Services are all about trust. Western societies are mature in the modern era, so naturally their services are perceived to be of higher value. Just think of the Big 4 accounting firms, and think about which Chinese audit firm that can come to your mind who can rival the Big 4. Or think of McKinsey, and then think about which Chinese consulting firms come to your mind. I doubt any names come into your mind.

It’s not that Chinese audit firms or consulting companies are not as good, but when people pay for McKinsey or KPMG’s services, it’s not just the “services” per se they are looking for, but also the fact that this is done by McKinsey. That logo itself carries a lot of value, even most of the value.

In the professional data and information industry I operate in, there are also similar issues which make this industry in China a tiny fraction of what it is in the West. I keep a separate niche newsletter about this called Data Currency. In case you are interested, below is the first essay of that newsletter:

Another major service industry, and perhaps the largest service industry, is healthcare. But here, it may just be the opposite. China’s healthcare industry is all about efficiency. In fact, perhaps because it is “too efficient”, its total GDP is nothing compared with the bloated US healthcare system.

Q: There is a lot of talk about purges in the PLA. Having family who’ve served in various nations’ military I’m aware of what a purge means there, which usually is the general being “fired” from his current assignment, given a pleasant job until the relevant MIC-IMATT figures out how they can use him to funnel more money their way in another position. In other words a purge is rarely a moment where criminal activities are punished by severe actions. What happens in the PLA when a group of generals are purged? Is it usually fatal to career, if not life?

A: In China, “purge” usually leads to various degrees of punishment, from imprisonment down to demotion to an extremely lowly rank, and is usually fatal to career. Death penalties are extremely rare though nowadays.

In a high-profile “purge” not related to the PLA, Qin Gang, who has been our Foreign Minsiter for a few months in 2023 before his “purge”, has reappeared again recently, showing not only he is alive and well but it’s possible his career may still have a future.

Q: Which of your subjects gets the most interest from readers?

A: I think you can have a rough sense from a look at the ranking of my most popular essays. Most of these articles focus on “narratives” and deep cultural barriers that lead to cognitive errors when viewing China. I call this type of content “mirror in a mirror” and have a whole tag dedicated to it now. One recent surprise is the article Breakneck, the big parade, and mirrors in mirrors, which falls along this line.

Q: Maybe you can write a post about foreigners studying in Chinese universities. For example, what would it entail to try applying to Tsinghua University with only English as a language and then studying there?

A: That could well be a future trend, as China’s universities have become increasingly more competitive globally.

Last week, as part of Baiguan’s first China Tour, we got to visit West Lake University in Hangzhou, one of the few new so-called privately funded research universities in China. They have many international students and faculty members already. We are really impressed. We will write about them in an upcoming post.

Q: How do you get the time to write? You have your own business and life, maybe even young children to raise. I used to have a blog, and it took a lot of effort. With children and now in a foreign country, I know this is so hard to find time.

A: I spent about 20% of my waking time writing. A lot of it happens in my spare time, such as traveling on the road, during weekends, or between business meetings. For me, the most energy-consuming part is to figure out the general structure and flow of my piece. Once that skeleton is ready, filling in the flesh is just a matter of time.

Another helpful device is that when I inevitably write something on social media, I am conscious that parts and bits of it can also be added to my longer piece. For instance, we organize a Discord community for paying subscribers of Baiguan, and I comment quite often in that community, usually responding to members’ questions. When I write there, I am always mindful that some of the writings may be expanded into a full essay. A lot of my essays come from this way. In a sense, I view social media as a testing ground for more structured works.

It’s also worth noting that I enjoy writing. Writing is my way of clearing out my thoughts and putting them into something concrete. Writing is my way of thinking. I view writing as a form of leisure, not labor.

Lastly, although I am busy with work, I don’t have kids yet. Perhaps when I have kids, things will change. We will see.

Q: An Asia Times article from Dec 4, 2023. reports that spitting, loud throat clearing and smoking have vanished from the streets of Beijing. Can you or anyone you know tell us more about it? Are these changes lasting? And, for them to happen, who did what?

A: If 20 years ago these uncivilized behaviors happened at the frequency of a 10, then at least in major cities, it stands at perhaps 2-3 at the moment. Not really vanished, but significantly less frequent than before. Smoking is still quite a problem, but in cities like Shanghai, no-smoking-indoor policies, which were only introduced a few years ago, have been well-enforced.

I think this transition to more civility is just inevitable, as China transitioned from a rural society to an urban one. You have to remember, spitting, throat clearing or smoking as you wish won’t be a problem at all if you live in a village, plowing your own fields.

Q: As a CEO of a Chinese startup, if you were to start going to your workplace by bicycle, how do you expect your colleagues, your employees, and business partners would react to it? And, would it make a difference if the bike is ordinary (mechanical) or an e-bike?

A: There won’t be much of a reaction. This is considered normal. There is no protocol on how a CEO should travel here. Maybe if my company is just not big enough. If I am a Fortune 500 CEO and bike to the office, I still don’t think people will be surprised. China has a long history of cycling. And nowadays, outdoor sports are also quite in fashion.

Maybe riding an e-bike to work for a CEO is slightly weird.

Thank you for your answers. For the sake of mutual sharing, my question about biking to work was directly inspired by a segment of Erin Meyer's business bestseller "The Culture Map" (2014), Ch. 4:

https://i.ibb.co/1tfQP8bm/Erin-Meyer-Culture-Map-quote-power-distance.png

Thanks a lot Robert for you post. Clear and human honest answers