The end of West's ideological monotony

A journey of double political awakenings of a young Chinese

This essay has been sitting in the corner of my draft box for a long time. Unlike other articles in this newsletter, this one is not about China, but about the West. So for some time, I struggled to find the right occasion to publish it. Seeing those people who don’t know much about China (such as Noah Smith) talking about China as if they were experts haunts me greatly, so I figure I’d better think twice about commenting somewhere I don’t come from, even though I did spend many of my student years in the West, and unlike Noah with the Chinese language, I can speak English and I read both historical and contemporary content in English.

Two things made me finally decide to publish this article now. First, to be totally honest, this article is not exactly about the West. It’s about how a young child in China became first enamored with the West, only to be disappointed later. It’s a story about myself. And just like how Noah represents how a whole lot of people in the West look at China, I hope by dissecting myself, you would also gain a valuable glimpse into how a considerable number of young Chinese like me have come to look at the world.

The second thing that prompted me was the failed assassination of Donald Trump last weekend, which could be a defining moment of our century. Barring any miracle, Trump’s second term seems inevitable, making me realize the West that I used to know might cease to exist any minute from now on. In that case, I will lose the target to critique and my writing will lose relevancy.

So I’d better hurry up now.

The Tweet

Originally, the idea for this article was prompted by a tweet.

On May 16, Mr. Lawrence Wong was formally sworn in as the 4th Prime Minister of Singapore. One X user, named Steven Glinert left this comment about the event:

I am not Singaporean, but I love the history of Singapore. I always say Lee Kuan Yew, the founder of Singapore is easily my top idol. Learning about Lee’s story, his words and his achievements gave the once 20-something me epiphany after epiphany. He is truly “a great man on a small stage”. In his and his many colleagues’ hands, Singapore was transformed from a post-colonial, resource-poor backwater just booted out of Malaysia, into one of the most prosperous and globally prominent economic centers in the whole world, all achieved with a reasonable degree of democracy and liberty for his citizens, high amount of human development, and a huge dose of common sense.

His son, Lee Hsien Loong, the 3rd Prime Minister, certainly had better resources to prepare himself to take the top job. But the top job is not an easy job, especially not for the Prime Minister of Singapore. It’s a high-pressure, demanding job that you need to devote your whole life to. And I think Lee the Son also did a terrific job. I watched many speeches he delivered over the years, and I hope one day our leaders could be as eloquent and as confident in expressing sensible ideas to their people.

But in the tweet by Mr. Glinert, all those achievements were reduced into a single dimension, that somehow the “Lee Dynasty” has impeded Singapore from joining the ranks of truly civilized nations, as defined and certified by the West.

You might not care about what Mr. Glinert said. But I find in this tweet a common pattern in the mainstream Western discourse: a singular complacency in handing out judgments to the world using a very narrow way of measurement.

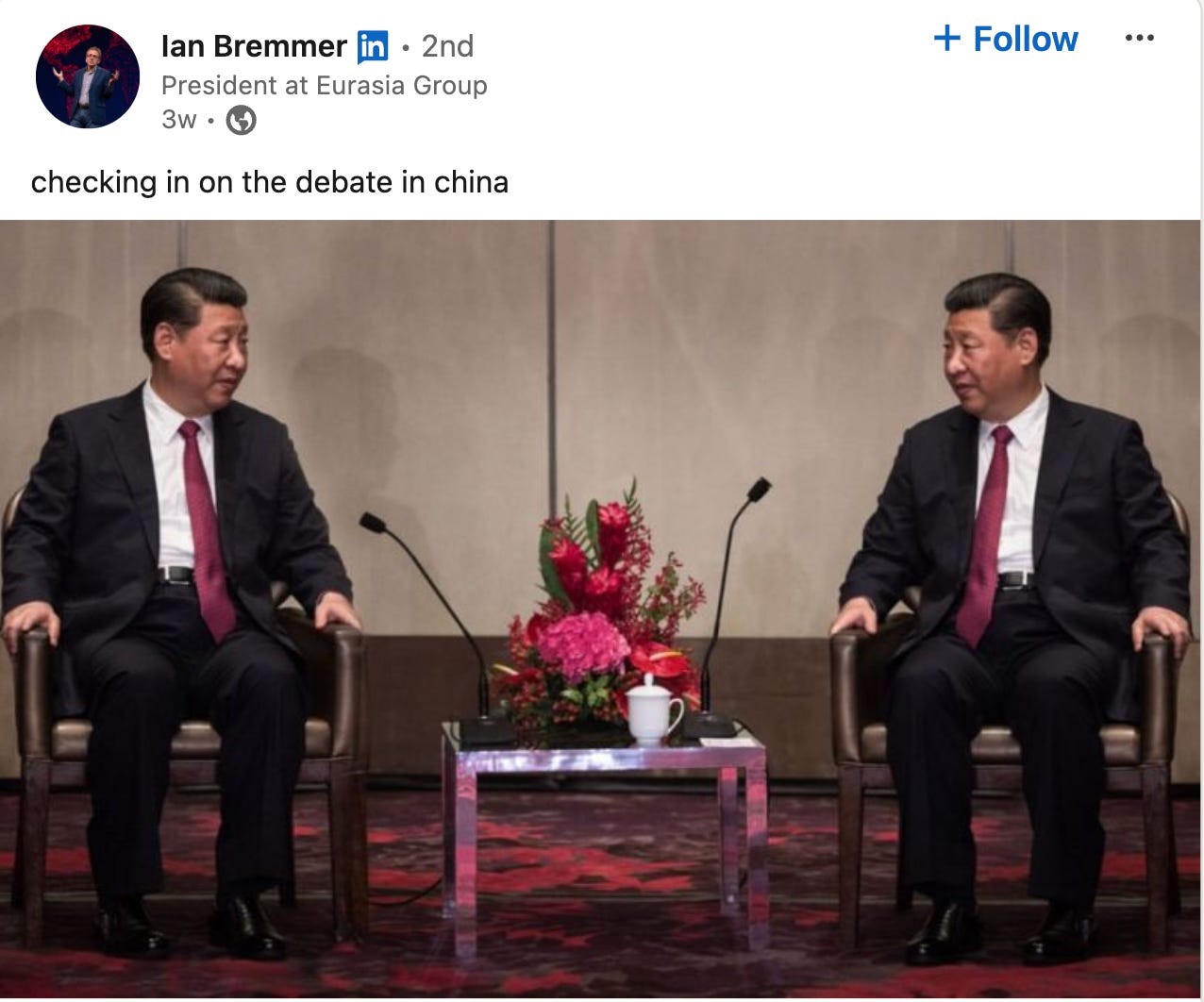

It’s a sense of complacency deep in the mind of Western elites. For example, just when Donald Trump and Joe Biden finished their depressing pissing contest that’s the presidential debate, Ian Bremmer of Eurasia Group, instead of reflecting on how the West has come to this point, posted this:

These tweets are like silent punches into my stomach. In an instant, my many memories, going all the way back to my adolescent years started to flash back.

My First Awakening

I was politically awakened, for the first time, when I was ~14 years old.

In that year, I first learned of Tiananmen Square. I was shocked to find there could be an event of such historic significance happening, at the time, barely 15 years ago, and I knew nothing about it till then. It was a bizarre and pummeling experience that I bet many of the more politically conscious members of my generation have gone through at some point in our lives.

It was also the same year when I really focused on learning English. Being a maverick, I managed to find ways (some are illicit) to subscribe to all sorts of foreign magazines. I remember my very first one was Newsweek. In the beginning, I couldn’t recognize more than half of the words in any article, but I labored through it with all means possible to the point when I could fully enjoy reading Fareed Zakaria’s great columns.

My favorite magazine during that period turned out to be National Geographic. In one month’s issue, I was gifted with a wonderful “Earth at Night” map which I hung on my wall till today. As a kid, I often stood there looking at it, aching and fantasizing about future global travel.

I also surfed the young internet for whatever kind of information I could find. I even bought an old-school short-wave radio and (secretly) listened to foreign radio transmitted across the high seas. At the time my favorite channel was the Chinese-language channel of France’s RFI, which is relatively balanced regarding China vs US, (unless it comes to French affairs). I hated Voice of America. It’s utterly boring. There was also a Chinese-language channel from DPRK, giving me glimse into the hermit kingdom.

For the first few years, what I saw and learned truly fascinated me. I started to learn about Western ideas and political philosophies. Liberty, democracy, rule of law, checks and balances, Adam Smith, Tocqueville, Jefferson, Rousseau, Plato… This beautiful variety of fresh ideas and new information made the paltry information I had access to in China pale in comparison. Toward the dreaded monotony and self-righteousness of the official indoctrination in China, I felt disgust, even anger.

This political awakening also coincided with my rite of passage as a teenager. And you could imagine how explosive that combo could prove to be at times. (My parents will painfully agree.)

I sincerely felt at the time, that indeed, as Francis Fukuyama famously claimed, the history has ended. It’s a matter of time before the whole world will converge into the same value system.

But has the history really ended?

My Second Awakening

At a certain point, I forgot exactly when, maybe at ~20, something started to bug me. Something seemed missing but I didn’t yet know how to describe it.

I felt that what I was learning started to be repetitive, and boring. The first publication that started to bore me was The Economist. It’s a curious publication that always seems to give you an expansive view of the entire world, but yet amazingly, an invisible hand always seems to be able to fit every event of the world into a single ideological framework. A protest happening in the Middle East? This is because of a lack of democracy. Indian economy not doing great? But their democratic institutions are wonderful. Modi is doing something right for India’s economy? But he is damaging India’s democratic institutions. Economic miracle in China? But one-party rule is too bad! Economic problems in China? Because of no democracy, of course!

Is the world really that simple? Shouldn’t the world’s problems be already fixed by now if that’s so simple? My dreaded monotony has come back to me again.

At the same time, my understanding of the world starts to flourish in more directions. I read philosophy, world history, Chinese history, economics, science, social sciences, history of science… I tried several businesses during college, but they went nowhere. I tried investing, which was quite fun. And the aggregate of all these learnings and trials of real life made me appreciate the complexity of the world’s problems.

This world is not for the faint-hearted. Hard decisions are being made all the time. There would not be any magic pill for the world’s problems. And once there was an attempt for a magic pill, disasters usually ensue.

Yes, the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution were such lethal magic pills. But so was the Iraq War. I never could wrap my mind around the Iraq War. Looking back, I see a combination of paranoia, moral hubris, and sheer ignorance that brought the Americans into a war which was presumably a magic pill that would bring freedom and prosperity to the ancient land of Mesopotamia. Instead, what you got was only pain and suffering for the people involved and the loss of a million lives.

Events like the Iraq War (and similarly the shock-wave therapy in post-Soviet Russia which essentially gave rise to Putin, and many other such episodes) ought to be important lessons that Westerners should keep revisiting and reflecting on the problems with their own political philosophy. Maybe we are missing something here? Maybe we should rethink our positions and start to reform them?

Instead, strangely, I almost never see people talking about events like the Iraq War anymore these days. It was certainly not “censored” in the same way that “Tiananmen Square” was censored in China, but I know it is still “censored”, in a more subtle but more effective way.

Some time ago I saw this video of Mr. Kishore Mahbubani, a former Singaporean diplomat giving an insightful talk at Harvard about this deeper format of “censorship”. (Gosh, how I love that small but sensible country.) I think this talk was viewed by far too few people in the West:

One thing that really surprised me, on the one hand, United States has the freest media in the world, the best finance newspapers, the best finance television stations in the world. But I can tell you this, as someone who travels 30 or 40 countries a year, when I come to the United States, and when I go to my hotel room in Charles Hotel and turn on the television, I feel I have been cut off from the rest of the world. Literally. The insularity of the American discourse is actually frightening. This is also true for the New York Times. This is also true for the Washington Post. This is true for the Wall Street Journal. There is this incestuous, self-referential discourse among these newspaper journalists, and they reinforce each others’ perspectives and end up misunderstanding the world.

What Mr. Mahbubani said entirely resonates with me.

Today, whenever I turn to read the same mainstream Western media that led me onto my journey 20 years ago, I am shocked to find that although I have evolved a lot since then, what I am reading seems not to have changed at all! For all this time, the same media seem only able to put on the same old set of lenses to explain the world. There is only one doctrine, one yardstick, and one principle to decide what’s good or bad: the Religion of Democracy and Freedom. Never mind about the importance of economic development. Never mind the importance of peace. Never mind deeper respect for rules and civility that may only flourish in an environment of stability and prosperity, and through good public education. All of these important topics pale in front the all-mightly Religion of Democracy and Freedom. You take this magic pill, you are cured. Refuse it? You are doomed.

I have suddenly realized the same Western media that used to amaze me 20 years ago, is sadly also a form of indoctrination. It’s, for lack of a better word, propaganda. Not just any propaganda, but a more dangerous form of propaganda in which the people involved don’t realize it at all!

What’s propaganda anyway? I have witnessed two kinds of propaganda in my life, so I think I have something to say here: propaganda is really just the systemic expression of any set of belief systems (aka ideology) that claims only this ideology is better than everything else. Sometimes, even facts and truth can be sacrificed for the sake of upholding this one ideology. But isn’t telling the truth (including the whole truth) what news media’s main job is all about? Since when does conformity to the same story become more important?

In this regard, Chinese propaganda and Western propaganda really don’t have much difference. The only difference is that Western propaganda is far more effective, that far fewer people question it, and that wars and suffering and human sacrifices could be brought about by this self-referential propaganda without people involved ever realizing it and ever regretting it.

My Renewed Perspective on China

If you are too married into the West’s ideological monotony, you might think I am ranting against the idea of democracy. Absolutely not! I love democracy. Democracy is good. Freedom is valuable. I am simply objecting to the idea that one set of ideas should take absolute precedence over others.