This newsletter will turn 1 year old tomorrow. As promised, I published the Master Plan of this newsletter last week and will pin it on my homepage for your future reference.

This post is fulfilling my other promise, which is to answer all the questions you have thrown at me. I will finish this Q&A in 2 parts. In Part 1, I will deal only with questions about myself. In the upcoming Part 2, I will try to answer those questions about my thinking related to China.

#1 Can you criticize Xi Jinping? Do you self-censor? Can I trust you if there are things you can’t say?

This is a classic baiting question, designed to corner the respondents into an impossible situation. It’s certainly not possible for the respondents to give an emphatic “yes”. If the respondents even hesitate a moment, they also prove the case of the questioners, which is that Chinese people live in a 1984 hell. This is how Victor Gao was made into a laughing stock by Mehdi Hasan. Often, the ill-meaning questioners can walk away with a smug smile and a reaffirmation of their superiority.

But is it really an impossible question? Not for me.

Let me answer this juvenile question with this mental model:

So there are 2 factors to consider here. Whether this is a public vs. private criticism, and whether it’s a criticism of Xi as the representative of China’s political system vs. criticism of Xi’s specific policies.

The second distinction is very important because China has a system where the symbol of power and the actual wielder of power are combined into one. For example, in a constitutional monarchy like Japan or the UK, the monarchs are symbols, while the prime ministers, representing the wills of the parliaments, wield actual power. Ruling parties and their prime ministers come and go, but the monarchs, and the union of the “imagined community” they represent, stay the same.

China’s one-party system, however, is unique in the sense that both “the symbolic” and “the practical” are one and the same, which is the Party. Sitting at the top of that party structure is one person, who combines the symbolic (the presidency) and the practical (as the head of the ruling party and the head of the military.)

When some people talk about “criticizing Xi Jinping” (such as when the Hong Kong fugitive asked Victor Gao this question) or “criticizing CCP”, they are really trying to attack the “symbolic” - the whole system of governance and ideas that Xi and the Party represent. They are really asking for the downfall of that system, the regime change. They would rather such kind of system does not exist in the world.

Well, let me answer this very plainly. In today’s China, this is not only illegal but very unconstitutional.

Let me read you the very first paragraph of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China:

Article 1 The People’s Republic of China is a socialist state governed by a people’s democratic dictatorship that is led by the working class and based on an alliance of workers and peasants.

The socialist system is the fundamental system of the People’s Republic of China. Leadership by the Communist Party of China is the defining feature of socialism with Chinese characteristics. It is prohibited for any organization or individual to damage the socialist system.

In this sense, asking someone in China to reject the one-party rule is equivalent to asking someone in the US to support the cancellation of separation of powers, or asking someone in Germany to deliver a Nazi salutation - all of these scenarios are just not very constitutional in their respective countries.

Many people in China are understandably not happy with this constitutional structure that we have. Some will express doubts and concerns about it in private. I have personally encountered countless such talks. Even I myself was a grumpy maverick when I was younger. But it’s important to note that nothing has happened to me or anyone participating in those private discussions, because China is not the 1984 hell many people imagine it to be. Moreover, if some people are consistently unhappy about China’s constitution, they will eventually vote by foot and choose to leave. Unlike North Korea, China does not bar citizens from emigration.

Now, how about the “practical”? Can Chinese people criticize the policies of Xi’s administration?

Oh yeah, this happens all the time. Go ask any taxi driver in China what s/he thinks of the economic policy, or of zero-Covid years, or of Ukraine, you will have an earful of all sorts of feedback. Heated debates about specific policies, both national and regional happen all the time. Frequent readers of this newsletter should not be surprised by the sheer number of instances our government stands back from unpopular policies.

There are two subtle nuances here.

First, certain policies concern China’s core issues and so become inseparable from “the symbolic”. The one-China policy is such an example. In fact, advocating for the independence of Taiwan, or Hong Kong, is illegal in China as governed by the Anti-secession Law. Will I criticize Xi’s Taiwan policies? I won’t. I can’t. (And in this case, I don’t even want to.)

Another thing to consider is that, counter-intuitively, the small folks in China have relatively more freedom to criticize policies, because nobody really cares about the voice of small folks anywhere in the world. Yet when people with actual influence engage in public debates, things get tricky. Any voice running counter to the prevailing policy that has gained too much volume runs the risk of being censored. This is not because those criticisms are not heard, but still because the “symbolic power” does not want to be challenged.

For instance, I have read countless very popular articles calling for a major stimulus program this year that eventually got censored. They were censored out of the fear that the massive attention they have generated may eventually be a rallying call for challenging and destabilizing the whole system. But they are still being heard. Have you seen the recent policy pivot?

(At this point, I can’t help but compare. It’s true that in the West, you have total and absolute freedom to talk shit about your politicians. But how many of our voices are being heard? Comparing a system where citizens can talk shit about politics with absolute freedom but the inability to bring out real changes, and a system that has limited freedom of speech but hear criticisms intently, which one is really worse?)

Long story short: I am a law-abiding citizen living in China. There are certain areas concerning our fundamental political structure I will not touch on. I will also be extra careful when I write about things that may be construed as being against the system, “the symbolic”. But there are probably only 10 out of a universe of 1000 interesting issues that are of this nature. For the 990 remaining ones, nothing is preventing me from making honest and useful comments.

Can you trust me because of this light self-censorship? You decide.

#2 Do you get paid by the Chinese state? What are your commercial interests in doing this?

The firm I control and operate does not get paid by the Chinese state, local governments, or even state-owned enterprises. As we grow, there is no guarantee we won’t have those clients in the future. But in general, we do not prefer to work with those types of clients if we don’t have to. The reason is simple: the sales process and payment cycles when working with those institutions in China are a headache, and our team has no experience in dealing with them on a commercial basis. Our business is too sound, and our skillset is too insufficient, for us to enter the state sector.

The newsletters currently only represent less than 3% of our total revenue. So direct commercial interests are tiny. We write our newsletters, because, first and foremost, we love to write. From a commercial perspective, it is also a smart business decision. Some of our institutional clients get introduced to our work through these newsletters. So it’s a subtle kind of marketing channel that not only we do not have to pay for it, we can even get paid by it.

#3 Why do you pick fights with Noah Smith?

I have said this before:

Because Noah represents a perfectly worded body of thoughts that mainstream Western elites have managed to attain about China. Some of those thoughts are valid, but most of them are simply based on cultural hubris and an uninformed understanding of a country they barely understand. So by critiquing Noah Smith, I essentially see him as the whipping boy for this whole group of people.

#4 You are a China shill. Prove to me you are not.

Let me ask this question first: can you imagine someone who genuinely supports most of the Communist Party of China’s policies?

I mean “most”, not just “some”, but “most”.

“Most” means more than 50%.

“Most” means if China is to hold a general election now and a polar opposite of the CPC appears on the stage as the contender, I will vote for the CPC. And I dare to say, the majority (in fact, a great majority) of people in China think similarly.

How else do you think CPC keeps power? How else do you think a minority of bureaucrats and a few hundred thousand PLA servicemen keep the vast majority of 1.4 billion people from toppling their rule?

If you can’t imagine such kind of people even exist, and if you can’t kill the fantasy in mind that, given a chance, Chinese people will revolt against their government, then of course you will treat CPC-friendly people as a “shill”, someone who must be someone else’s payroll for saying things.

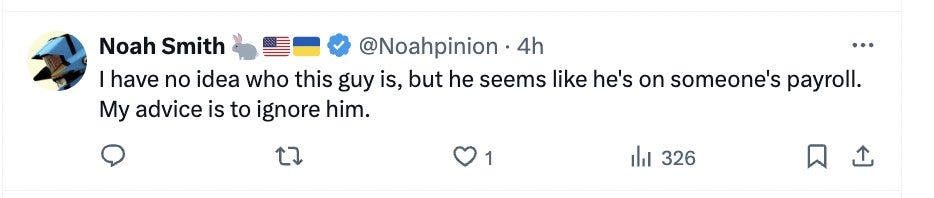

For instance, this is what Noah Smith said about me:

#5 Why do you always make fun of Wei Lingling?

I actually like and respect many Western journalists’ work about China, but not Wei Lingling (she was not even born Western). Wei Lingling is the mirror image of People’s Daily, only that she doesn’t realize it. She represents a form of bad journalism in which she already reaches a conclusion before writing anything, and will try to fit whatever information she can find to fit that conclusion.

Her main narrative of now is “Xi bad”. China is figuring out how to regulate data? Xi is locking the country inside a black box!

China’s economy is sluggish? Because Xi is bad.

China’s economic policy is pivoting 180 degrees? This shows the rigidity of China’s system, all because Xi is a bad dictator!

I dislike this type of person in the same way I would dislike a red guard had I lived through the Cultural Revolution year: a crusader, grand-standing, always believing in her own moral superiority, fitting everything into an ideological angle, putting ideology first, facts second, useful knowledge for her readers third. I dislike ignorance and lack of imagination, especially when they are coated with ideological certainty.

I am also not sure what value this type of journalism can bring to the table. Criticisms are great, it should be part of what journalism is about. But criticizing at every opportunity, criticizing out of proportion, telling half-truths but not the whole truth just for criticism's sake, and criticizing just to feel good about oneself, not only discredit the endeavor but can actually do more harm than good for the stakeholders.

#6 Have you ever written a blog or similar publication in Chinese? How did you come to see your primary interest as being writing in English rather than in Chinese?

In the last decade, my only other “blog” is my WeChat blog, now titled “意外的CEO” (The Accidental CEO), where I mostly write about business management and China’s data and information services market in Chinese. For instance, a very popular article in Baiguan, China’s venture capital industry is dying, was originally written in Chinese on my WeChat blog, 5 months before that infamous FT article which actually shared the same core message of mine.

You are right in that my primary interest in writing is in English. There are two reasons contributing to this. First, believe it or not, I feel much more at ease writing in English than in Chinese. I love how well-structured a Western language like English is, so I can write much more clearly and make more accurate arguments in English than in Chinese. The weakness (as well as strength) of the Chinese language is often in its poetic vagueness. (That’s why I also fell in love with learning German 2 years ago, because German is really “structure and accuracy” on steroids).

The second reason is that my thinking is not unique in the Chinese-language world, so I don’t think I can add too much value to the discourse. In the English-language world though, I see a severe under-supply of content that prioritizes empathy and understanding over confrontation and ideology, so the potential impact of writing in English is much bigger for me.

#7 Do you use VPN to write and publish behind a firewall?

Although this site itself, “china-translated.com” is not blocked (yet) by the Great Firewall, the many sites that I will rely on to write, ranging from Google, to Wikipedia, to ChatGPT to mainstream Western media sites are blocked.

This is as much as I can reveal to avoid legal troubles. Using a VPN is illegal in China, although prosecution is extremely rare.

#8 Do you daydream of significantly contributing to the improvement of China's foreign policy?

I think I already am, in my own way.

At the risk of exaggerating my actual influence: there are many foreign government officials and diplomats reading our newsletters, so my writing might get into the calculus of some policy-thinking. The non-government readers who read and share my content also will help shape the right media environment for a less confrontational relationship between China and the West.

Indirectly, having such a strong and growing global following may also give me credit and access to express my ideas on how China can improve our own practices.

#9 How do you look at the possibility of your becoming a member in a political party, if you aren't already? Is there any party that strikes you as somewhat attractive?

I am not a member yet of any political party. As a young maverick, I was one of the fewer than 10 students out of 600 in my high school who refused to join the Communist Youth League, which was almost like a social norm in China’s high schools. It’s the equivalent of refusing to join your graduation prom. Weirdo!

As a Hong Kong permanent resident now, I see no recognizable path to join the Communist Party of China. I may want to join one of the 8 so-called 民主党派 minor parties, a special mechanism for the CPC to absorb input from non-party elements who want to keep some level of distance. (By the way, it’s what the much-demonized word “united front work” is all about.)

The most plausible option for me though, is one day to join a political party in Hong Kong. I have already outlined the principles I look for in this party in Part 2 of my “Hong Kong is not over” article. And if by the time there is no party that fits my principles, heck, maybe I will start a new one.

#10 Who is your favorite Marxist revolutionary?

Hmm… “Marxist revolutionary” is not the category I often look for my favorite people in. One of my favorite political figures, Lee Kuan Yew, was a famous anti-Communist. But if the question is about which founding father(s) of the PRC whom I like the most, here will be my rough answer:

Deng Xiaoping, for his resilience and fearlessness to always do the right thing;

Zhou Enlai, for his purity and genuine care for other people, despite the odds;

Mao Zedong, for his willpower, romanticism, poetry, and the sheer level of achievement that is really unparalleled in China’s long history;

Peng Dehuai, for his courage to speak truth to power, even when the Great Leader was obviously in the wrong, sacrificing himself along the way.

#11 What makes you give a "Like" to a comment or NOT give it? In any case, the distribution of your 'Likes' often leaves me puzzled, as it appears somewhat random.

Substack elevates comments with more likes (and especially likes by the author) to the front row. I “like” comments in order to promote them for a variety of reasons. Sometimes they fill in necessary gaps that I have left open. Sometimes they are important criticisms to counterbalance my work.

[There is no further content in the “paid” section below. I put up this wall so that this post can rank higher on my “most popular” list, since Substack’s algorithm prioritize paid articles over unpaid ones]