Hi everyone! It has been another slow week for China. There are only a few things I want to talk about, but I am afraid they can’t make up a whole post. Besides, I have fallen ill so I would need a few days to write something heavy. On the other hand, tomorrow will be the Taiwan election, an event all of us are watching quite closely. So I decided again not to do a typical weekly review format this week. I will just group events of 2 weeks for next week’s review.

In this post, I will answer some of the questions and comments regarding Part 1 of my “Noah Smith is Clueless about China” series. I will write it in a Q&A style, with questions in block quotes and my answers below.

[I have gained some new subscribers after launching the Noah Smith series. If you are not familiar with me and why I write, please check here. For what unique things I can bring to the table, check here.]

China payment panel data

A little advertisement before I start: my team at Baiguan/BigOne Lab published a comprehensive study of Chinese consumer spending behavior by collecting WeChat and Alipay payment statements from consenting consumers. Compared with traditional user survey-based research methods, such methodology has the benefits of being un-subjective, unbiased, and comprehensive. It would be a great tool to look at research topics such as:

Structural movements in consumer wallet shares

Tracking of deflationary pressures and consumption downgrade

Competitive landscape and user cohort analysis between brands in retail, beauty, dining, hotel, transportation, and education sectors.

We plan to do this kind of study on a quarterly basis. If you are interested in subscribing to this dataset, please request for demo at BigOne Lab.

On “China is not insecure”

From Christian D Manley, who wrote long and very thoughtful comments (and challenges) for me:

Q:

“China is not insecure.” What then is the 100 years of humiliation taught in schools and spoken about in the media?

Robert:

The humiliating years are indeed one of the handful of moments in Chinese history where there was a real existential crisis. As I mentioned in my little explainer note to last week’s post, this is the period that jolted Chinese people to become the China that we experience today.

However, much of the energy here is still driven inward. Every time we talk about this period of humiliation, the most frequently chanted conclusion is almost always: “落后就要挨打” or “You will get beaten up as soon as you lag behind others”.

Please pay attention here. We do not say, “Once we are stronger we should beat up our enemies” or “Stop getting weaker and we shall kick colonial powers’ asses”. Instead, it’s much more inward-looking and much more passive.

What’s the real lesson from that humiliation? Don’t get beaten up. How not to get beaten up? Don’t lag behind others. The ultimate lesson from 100-year-humiliation becomes a call for self-improvement… Isn’t that a very Chinese thing to do?

Q:

“There is no great war on the horizon. Leaders won’t do the same as Stalin.” I am not sure, but many in the US fear there will be. Some in China worry too. There have always been worries concerning this. Granted, again, this is why we must continue talking!

Robert:

Purely from what I have experienced, way more Americans than Chinese are imagining a great war coming. For example, if you search for public speeches and online discourses, you see way more references to WW3 in English-speaking space. Living in China, it just doesn’t feel like we are preparing for a war. We have other problems to deal with. When consumers spend less, I don’t see anyone citing the possibility of a war as a reason.

In recent years there are indeed more mentions of “security”. But it’s still very inward-looking. It centers on ensuring basic needs such as food security and energy security to withstand any contingency situation. It’s also nothing new. I remember similar policies when I was younger. As the Chinese economy gets so big, the stakes are higher now, and more people around the world pay more attention to China, and it’s only natural for the message to get amplified.

From Yaw, who, by the way, writes the wonderful Yaw's Newsletter, my go-to source for Africa-related news and analysis right now. Highly recommend!

Q:

However, don't you think China facing an existential threat from America? You said "No!" to the question. "Is China facing an existential threat?"

Were you not threatened by Obama's "Pivot to Asia" strategy and America's further actions in the region?

Like America giving Australia a nuclear powered submarine and America "defending freedom of navigation" in the South China Sea (aka arming Taiwan and increasing military and navy presence in the region).

Robert:

It’s a threat, but nothing existential.

During the Korean War, when the Americans almost reached the Yalu River in 1950, at a time when the PRC was just founded, that was an existential threat (I will talk more about existential threat from the northeastern direction later).

When China and the Soviet Union skirmished on the border in 1969, and when the Soviets amassed over 1 million troops at the border with war plans to drop nuclear bombs on China, that's maybe the biggest existential threat. To prepare for the apocalyptical war with the Soviets, China even built mankind’s largest doomsday project in the southwestern hinterlands.

But "Pivot to Asia"? Sounds just like part of a healthy competition. People on the streets do not feel threatened by this. We don't live like we have an existential threat going on.

There were also episodes in China-US history that were way more explosive than today. For example, not many Americans today remember the Chinese lives that were killed in the 1999 NATO bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, or the 2001 Hainan Island Incident because at the time China was much weaker and deserved much less attention than today. But from a Chinese perspective, those episodes caused a much larger emotional outrage than anything we are seeing now, and we still managed to live through that.

Taiwan is a separate issue. Whether China can handle the issue well can be existential. I will touch on this topic later.

From Wije :

Insecurity: Beijing might be overconfident in dealing with the small countries, but that doesn't mean it feels secure. Why is the CCP so secretive? How come Beijing gave zero transparency when conducting its recent purges (contrasted with the current public fiasco in the US Defense Department)?

This question of CCP secrecy is far more important than whatever corruption in the military.

Robert:

People who know me know that I am always an advocate for more transparency (for example, here).

Another thing I talk about often is the quality of talents in the civil service force (compared with, for example, Singapore). The thing is, transparency is also hard to manage. If not done well, in a “low-trust” society like China, transparency could only lead to more distrust and confusion. So for mediocre people in a gigantic bureaucracy, often the safest choice is to stay silent. (I will talk about the “low-trust” nature of Chinese society one day, it’s a fascinating topic.)

I recently read an interesting book on the YongZheng Emperor (1678-1735) by Jonathan Spence. Spence described an emperor who wanted to be very transparent to his people. He wanted to publicly explain many of his ideas and motives in order to dispel a vile rumor about him killing his father. But in the end, the whole effort was very counter-productive. People just assume foul play. I think the ideas captured in the book are still to some extent relevant today.

I think China is improving in this regard. At least now the idea of transparency has been upheld. At least the government has to pay lip service to it in principle. Before, not being transparent is the norm. Now transparency is the norm.

I am only talking about broad concepts of secrecy vs transparency here. In this particular case, however, since this has to do with sensitive military and espionage matters, it’s reasonable to assume we will not know about what exactly happened for a long, long time.

On “China is not expansionist”

Also from Christian D Manley :

“China is not expansionist. Expansionist empires use “us v.s them” phrases.” What are titles like this then: https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1195495.shtml? I am not saying this shows China is expansionist. I am just saying us v.s them language exists, as it does in the US. Again, this is why dialogue between people is important. I do worry that Chinese companies going abroad sometimes do not recruit local talent. This can be bad for everyone, as are European and American companies going to China who do not listen to their Chinese colleagues for advice on the market.

Robert: Although “us vs them” narratives do exist in China, I still need to point out that we do not owe our existence (or our “reason for being”) to such narratives, in the same way, say, Nazis owe their existence to the subjugation and even extermination of other races (a very bad example, but I hope you can get my point here). Without such a narrative, we can still survive pretty much intact. It’s not something that defines us. The Global Times story you have quoted looks to me like an attempt (not necessarily a successful one) to withstand the high-pressure international environment in a Trumpian world, but people in China do not draw our source energy from these stories.

However, I agree 100% that dialogue between people is important. I also agree that many of our media organizations’ ways of expression, well, how should I put it, have ample potential for improvement. (If you think I am better at communicating this than they do, definitely tell them if you have access to them ^_^)

Q:

“China’s leaders said it will have a peaceful rise.” Just because someone says something, especially politicians, doesn’t mean they will keep that promise. Plus, what is the Art of War? Should we ignore all the language in there about deception?

Robert: Yes, deeds are more important than words. And again, here I am only stating my belief or hope, rather than something that can be proven by watertight evidence. It is very subjective. Listen to me at your own peril.

Still, 4 generations of leaders repeating the same mantra is not something to be shrugged off. Those words affect how people around them. It’s the same words that those people are also hearing and they will work about their jobs accordingly. You can say something publicly while doing something opposite, but only once or twice. That can’t be sustainable for half a century. Also, practically speaking it is almost impossible to have a hidden agenda for global conquest for this long without somehow getting leaked. Conspiracy theory on such a gigantic scale is not feasible.

I also wish to point out that those leaders are not just expressing their own views, but they are really only expressing the collective preferences of China as a nation.

People tend to get wrong about cause and effect in China. Most of the time, it’s not because a certain leader wants something, and then something just happens. But rather the other way around: that something is ripe to happen, and the leader exists to express it, set an agenda for it, and formalize it. (Please refer to my previous discussion of the “dictator” comment by Biden)

Talking about Sun Tzu’s Art of War, also remember the highest principle from the same book: “The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.” (不战而屈人之兵 善之善者也 ) You see, the cultural strain for disliking the war has already been with us 2500 years ago. War is just not cool.

And by the way, China is very consistent about what can trigger war. I think you should pay more attention to what has been said publicly over time, rather than always prioritize guessing the behind-the-scene motives. My experience is that although you can hide some details about your thinking from others, the fundamental truth about the “core matters” is always wide open for everyone to see. The easy way is often the right way.

Q:

“Tianxia was peaceful.” What were the wars between Tang and Guguryeo and then with Silla after they broke their alliance?

Robert: No, I didn’t say Tianxia was peaceful. There are many wars. I would be absolutely disingenuous to say China did not fight expansionist wars against neighbors.

But again, as I said, those are exceptions that proved the rule.

Take the war with Guguryeo you mentioned as an example. That war didn’t start with Tang, but the dynasty before it, the Sui. As I said last time, it’s the same failed war that led to the downfall of Sui. When Tang came to power, the famous Taizong, one of the greatest Chinese emperors, took over the baton and tried very hard. He also failed. He even died before could go on another conquest. It was the army of his much less famous son Gaozong that eventually finished the job when Guguryeo itself was in the midst of a civil war.

In each of the wars between Sui-Tang and Guguryeo, there was no lack of advisors who advised the emperors against military action. For example, top official and famous calligrapher Chu Suiliang褚遂良 advised against war with Guguryeo but was punished because of it. Those pieces of advice were all recorded by official accounts. Given the official history was kept by the scholar-officials themselves, you know what’s their stance on foreign aggression.

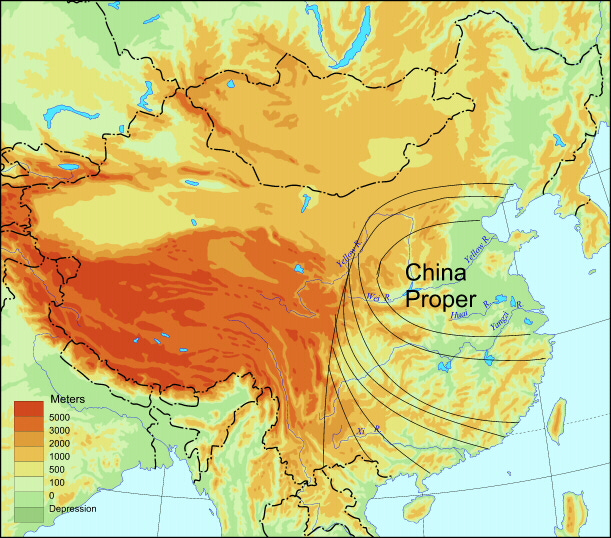

[An interesting side note is why the Sui and Tang Dynasties cared so much about Guguryeo, a powerful state occupying a big part of today’s Northeast China and the main parts of the Korean Peninsula. The wars lasted for ~70 years. Some historians even compared this series of wars to the Punic Wars between Rome and Carthage. One really interesting thing about China is that, most of the time when China faces an existential threat, it’s usually coming from the Northeast direction. For example, it’s the Khitans from the Northeast that weakened the Song Dynasty. The Jurchens from the Northeast in turn destroyed the Khitans and the Song. The Manchus from the Northeast destroyed the Ming. The Japanese first captured the Northeast (Manchuria) and invaded China proper from there. Even during the civil war, communists seized the Northeast first and afterward sped towards victories elsewhere. I don’t completely understand why that’s the case yet, but I guess there must be something quite important about that region.]

Similar dynamics also played out in other regions. For example, the uneasy historical relationship between China and Vietnam is an interesting case. The Ming dynasty did occupy Vietnam once, but that rule only lasted 20 years from 1407 to 1427. It’s simply not attainable.

Another interesting example is Yunnan, between 937 and 1253, that place belonged to the Dali Kingdom. For all of the Song Dynasty’s history, the Dali Kingdom was independent. It was only until the Ming Dynasty that Yunnan was formally incorporated into China. Afterward, the jungles and mountains of Yunnan mark the farthest extent of the reach of Chinese power in the Southwestern direction.

You could argue, that if not for geography, China would also have ended up with global expansion ambitions. That could be true. But it’s a pointless argument. We are who we are. The geographical constraints have shaped us, and led us to this “imagined reality” that’s called China today: a country with a rooster-shaped border cornered in this particular pocket of the world, with no strong territorial interests elsewhere.

from Wije:

Expansionism: I agree that the PRC generally doesn't resolve int'l disputes with force (in this way it's distinct from Putin's Russia). The PRC definitely doesn't want a war with the US. However, Yang Jiechi wanted us to know that “China is a big country and other countries are small countries, and that’s just a fact.” He deserves praise for his honesty.

One of my grad school classmates was a Chinese diplomat, and once he explicitly told us that it's better to be feared than loved. He certainly does not speak for all Chinese, but I hope you'll forgive me for believing that his views are closer to the mindset in Beijing than yours are.

I agree with you that the Tianxia system as *currently* practiced demonstrates overconfidence, not insecurity. However, I don't see it in benevolent terms. In return for access to Chinese markets, technology, investments etc, supplicants have to give up part of their sovereignty. This is the model in place from Myanmar to Indonesia.

Robert:

That Yang Jiechi comment, if true, is a typical example of the “Tianxia mindset”. As I said last time, I think this is a problem that we need to fix. We need to figure out a way to be respected while treating others as equals.

There are definitely different schools of thought here. From what I gather from my friends who are similar to the “diplomat classmate” that you have mentioned, the mainstream idea is to be “loved”, not to be “feared”.

Again, correctly diagnosing the nature of the Chinese mindset to be that of “over-confidence” instead of an “insecurity” issue is the crucial first step towards meaningful engagements and criticisms. For instance, instead of wrongly thinking of China as this expansionist hegemon and letting the situation spiral into unnecessary armed conflict, you should tell China that if we really believe in the idea of a “shared future of humankind”, in which case being patronizing to others is both stupid and counter-productive. It's the line of criticism that can actually be heard and be productive in improving things. Hold us accountable for who we aspire to be, not for who we are not.

On Taiwan

From Peter Angel:

I feel like you didn't touch on the thing that is core to Noah's thinking about China-US conflict: Taiwan. As fair as I can tell he thinks that China has gotten much more powerful, and has a somewhat bellicose attitude about the island and this could lead to a broader war.

Robert:

I will touch on Taiwan if I ever get to write the Part II of this Noah Smith series. But expect me to take a long, long time writing about this. This issue is inherently divisive and I have to strike a fine balance between the practical and the emotional.

Fun & Trivia

From yigit:

Very tangential comment but the way the prigozhin revolt absurdly fizzled out with the non-exile and all I'm finding it hard to believe that there'd be an reasonable equivalent to it in Chinese history

Robert:

It’s always great fun to make historical analogies!

In Chinese history, many armed rebellions, even armed rebellions by mercenaries were very, very common. One of the most famous rebellions was the one started by General An Lushan, a semi-mercenary of Persian and Turkic descent. His rebellion sent the glorious Tang Dynasty off the cliff.

And you made a great point here. Although armed rebellions were very common in Chinese history, the way the Prigozhin rebellion ended was very bizarre.

The closest example I could think of is maybe the Xi’an Incident of 1936, in which General Zhang Xueliang rebelled against and held hostage Chiang Kai-shek, the No.1 guy at the time, for a few days.

General Zhang was the “King” of the Northeast but he lost his home base after the Japanese invasion, so his army was stationed in Xi’an almost like a mercenary army. Just like Putin and Prigozhin used to be great pals, Chiang and Zhang used to be sworn brothers. Like Prigozhin who was ordered by Putin to fight against Ukraine, Zhang was ordered to fight Chiang’s archenemy, the communists. The Soviet Union played a role in resolving the incident, just like Belarus who played a third-party role in the Prigozhin case. Like Prigozhin, Zhang later gave up on the rebellion and willingly went back to Nanjing along with Chiang. He was immediately arrested by Chiang in Nanjing.

There is a key difference: unlike Prigozhin who was killed just a few months after the rebellion, General Zhang was house-arrested for almost 3 decades until Chiang’s death in 1975. Eventually, he got to die peacefully in Hawaii, at the age of 100. Unlike the Russians, even for a treasonous rebel, the destruction of his corporeal existence is not fashionable for us.

In terms of insecurity, I agree this is a gross misinterpretation of a phenomenon which may well be unique to China. In my more than 20 years in China, 1988-1993 and 2003-2019, I felt throughout, that particularly Han-Chinese people take enormous pride in their country, perhaps one may call it love, and they desperately want this love to be shared by others and therefore strive for appreciation and recognition, more than any other people, IMHO.

They are very receptive to flattery, if it is about China. It is neither superficial patriotism, dumb nationalism nor simple pride, it is not religion or superstition, it is something else.

There is no better way of frustrating a Han-Chinese than withholding recognition of China's whatever. They genuinely do not understand, if someone does not appreciate at least some features of China. The uniform, unison, 100% predictable reaction is "you don't understand China", which may well be deemed the worst possible level of condemnation.

On continuous paise and recognition, you will eventually get upgraded from 老朋友 "old friend" beta to 中国通 1.0, "China expert", the highest level a foreigner can ever attain, short of becoming a China citizen. Unfortunately, this title may well include Stalin's "useful idiot", so the default old friend beta version is the by far more comfortable title you want to carry.

This, lets call it "neediness", is currently also expressed in ever lighter visa requirements for foreign travelers to China. While on the surface this may not be viewed as something special, such a retreat of China's overbearing, kafkaesque bureaucracy is a really big deal in China. The low numbers of travelers expressing disinterest hurts and worries China's government more than one may think. They want travelers to come to China and appreciate it. Absurdly, foreign travelers flocking to China may well be a measure of validation of government.

Whatever all this may be, it is definitely not an expression of insecurity.

Ok, upon seeing these questions and objections, here are my own - note well, some of them are quite minor:

Robert: "China is like this entitled brat in the school, [.......] he can act foolishly angry. "

Do you really mean to imply that China can act foolishly angry on the international stage?

Is open show of anger in accordance with the morality of 'saving face'?

Robert: "You can’t persuade someone in the 1200s that the Earth is round as a ball [...]"

It is a historical myth that medieval Europeans generally thought the Earth was flat.

Robert: "There are some famous Insecure-Expansionist Empires in history, such as Nazi Germany, Soviet Union, Imperial Japan, and, cough cough, certain big country located to the north of China "

This remark simply shows that your understanding of the Soviet Union and modern Russia is grossly distorted.