3 principles for a small country to survive great-power competition (Part 1)

A travelogue to Georgia (the country)

[This is a free post. Ideally, I would want to limit the comment section to only my subscribers (both free and paid subscribers), but Substack doesn’t allow this option. So the comment section for this post is free for all. There is only one rule to observe here: be civil]

This is a travelogue as requested by a reader poll I conducted 2 weeks ago. I was ready to write it when only 100 of you asked for it. It turns out that 181 people have joined the poll, with 87% voting yes, so I am more than obliged to finish this as promised.

When I conducted the poll, I was first reluctant to write about it. After all, this is about my vacation to another country, but this newsletter is about giving you useful insights about today’s China. Yet, by the end of my trip, I realized there was more connection to this newsletter than I originally thought.

This travelogue will be made up of 2 parts. In the first part, which is this post, I will document the trip itself.

I will first carefully introduce with whom I traveled this time. This is because I am at the stage of my life when I believe it’s the people you travel with that matter in any travel, more than anything else. Without this part, traveling risks falling into a mere consumerist trap. This is especially true for our time when AI and hyper-digitization can bring any place in the world to your fingertip at any time. So increasingly, it may feel no longer necessary to travel abroad, if not for the people who go with you.

But I do think it’s still necessary to travel. There are just crucial details that you won’t get to experience unless you are physically there, which you will see from this account.

In the second part, I will deal with the title of this article. Throughout the trip, I kept thinking about this question: what makes a small country prosper in the age of great-power competition? What are the do’s and don’ts? I really think Georgia’s experience sheds some light on this topic, even though I may be no more than a hapless tourist.

I can’t finish this article in one go, so I have to split it into two. If you like to read this the more serious Part 2, subscribe and stay tuned for the next part.

The team

This trip happened quite suddenly.

Ever since I joined (and later took charge of) this data and research company in 2019, I have never done a proper overseas vacation. Covid has done its part, for sure, but it’s also the mindset of being forever on the job. So when a friend, whom I have known for more than a decade but haven’t seen for 5 years asked me last month whether I wanted to spend a week in Georgia, I thought to myself, heck, maybe I should give myself a break. Maybe this is the moment.

So I happily marked the trip on my calendar, and despite catching a fever right before it, I was fortunate enough to recover just in time and made it.

One key reason for me to make this decision so quickly was that this was not a totally random trip: I went in with a group of friends and friends of friends. It’s always fun to travel to a completely new place with friends, old and new. Better, 3 of them have already been to Georgia before and wanted to visit again this time. It’s great to just free-ride on their experience.

Our team was made up of seven adults and one 5-year-old. The friend who first invited me was a friend I knew in pre-college years. 2008 was the year when maybe only no more than 2000 high schoolers in China applied for US colleges. Many members of our cohort had no way to learn about college applications, so we self-helped in our internet discussion board, inadvertently creating a unique situation where students of similar backgrounds from all across China bonded together. We looked more like each other than we did with our own high school classmates. So it was as if we all studied in a massive, virtual high school and we became “alumni” of that school ever since. 2008 was also the year of a massive earthquake in Sichuan, China. My girlfriend and I joined the disaster relief volunteers. At my first stop in Chengdu, I asked my virtual “classmates” on whose couch we could stay for a night. The friend offered help, and that was my first time meeting her in person. I will call her the Romanticist, for her passionate taste of Soviet memorabilia.

Coming together with the Romanticist is her husband, whom I would call the Engineer. He was born in Nanjing, the same city where I was born. But at 9 years old he moved to the United States, when his English language skills didn’t even go beyond the alphabet. During the classes, he couldn’t understand a thing, so spent time reading The Romance of the Three Kingdoms (the Chinese version of course). But after only 1 year of hard work, and being bullied, he won in his school’s spelling bee competition. So yes, he is a genius. Later, he became a naturalized US citizen, went to one of the best science & technology universities in the world, then to a big Wall Street quant fund, went to tech companies, became one of the original co-contributors of Pandas (something all data people must have known), and now he was in the second year of founding his own AI infrastructure company.

I only met the Engineer once in 2019, at his wife, the Romanticist’s birthday party (we had Georgian wine during that party by the way. This cute couple really loved Georgia). We immediately bonded. The way he talked and thought about things was so familiar to me. Our personalities are almost exactly the same. I sometimes wonder if we are living each other’s life, in a parallel universe.

The 5-year-old is their kid. 5 years ago, at that birthday party of his mother, he was just a small bundle. Now, he is a handsome young boy. Quiet but sharp, able to speak English, Mandarin, and conversational French, he is easily THE smartest 5-year-old I have ever met and the most pleasant surprise of this trip. And he is not the arrogant kind of smart. Quite the opposite, he is the “deep”, unassuming smart, the kind of smartness that can connect unseen dots, and easily cut through the subtle half-truths told by adults. He also has a unique taste for music. He asked for classical music while I drove. The biggest amazement was when he recognized and hummed to the tune of one of my favorite songs, Zu Asche, Zu Staub of the popular German series Babylon Berlin. It is a dark song that requires some acquired taste to appreciate, and this young boy seems to have already acquired such taste. I will call him the Prodigy.

The other 3 members were all acquaintances of the Romanticist. I first met one of them also at that birthday party. At the time, he had just quit his high-paying finance job in Hong Kong and started his own software company. At the height of the venture capital craze in China, he was funded by a stellar list of who is who in China’s VC space. Now five years in, he was thinking about unwinding the business. He was tired, just like the majority of entrepreneurs I know in China. But I will still call him the Founder. In fact, being battle-hardened for 5 years gave him far more credit for this title than 5 years ago.

So, as you can see, we had 3 CEOs in this group. Having a “CEO ratio” of as high as 3/7 was also a key incentive for me to decide on making this trip. I picture us having some warm coffee by the fireside, staring at the snow-capped Caucasus, sharing our stories and lessons with each other, or just offering some emotional support. There are things only the few people who have shouldered the ultimate responsibility for an organization understand, so I jump at all opportunities to build rapport with our kind.

I didn’t previously know the last 2 people, but I was glad to be acquainted this time. One was a science professor in Hong Kong, but his knowledge of history and culture was vast. He also had a knack for imitating all accents and languages. For most of the trip, with his non-stop monologues, he served as our free tour guide. I would call him the Professor. And then there was the Lawyer, a soft-spoken woman who practiced corporate law in Beijing. Finally, there were also me and my partner.

Before going to Georgia, all of us made a 9-hour transit at Urumqi. It was also my first time visiting Xinjiang, so of course I took some time to get out of the airport, had some delicious halal barbecue, and visited different bazaars. This city looked at the same time familiar but strange to me. Many architectures and road designs made it just like any other Chinese city. But the Uyghur scriptures on road signs, the mosques, and people of obviously different races walking on the streets and co-existing also made it very different. The Engineer, who is an American Chinese, visited Xinjiang a few years ago. He told me that the city then was heavily fortified, still reeling from the interracial violence a few years back. Security checkpoints were everywhere on the streets, with only a few hundred meters apart. This time though, we almost never saw the police. The security checkpoint at the entrance of the Grand Bazaar, conducted by a few Uyghur-looking guards, was the only one we had to go through. Why is that? What has changed? I will leave you with your own answers.

Tbilisi

Before I started the trip, the few things I knew about Georgia only included:

It’s the birthplace of Joseph Stalin. Bizarrely, most of the big modern “empires” seemed to have been led by someone hailing from the fringes of that empire. Napoleon was Corsican, which was more Italian than French at the time. Hitler was not German, but Austrian. And then we have Ioseb Jughashvili, a former Georgian bank robber, a frequent tourist to the Russian gulags, a Bolshevik, General Secretary of the Communist Party of Soviet Union, a red tyrant, a mass murderer, but also the nations’ protector in the apocalyptic struggle against German Nazis. The pseudonym he was better known for, “Stalin”, means steel. He was a man of steel for the Soviet Union, and for Russia. But he was a Georgian.

It is a former Soviet republic, but now has an uneasy relationship with Russia. There was a war in 2008, a mini version of the 2022 Ukraine war. Georgia, almost 1/10 the size of Ukraine by all accounts, lost that war. After that, the separatist regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia gained de facto independence, backed by Russia, but recognized by only a few Russia-friendly countries in the world. They are not recognized by China.

It has great wine and is one of the origins of wine.

It is along the Caucasus, so presumably has great mountain views. I know friends who went there skiing in the winter.

This was as much as I knew when I landed at the Tbilisi International Airport.

Passing through the customs, 2 things immediately struck me. First, the airport looks so small, smaller than any airport I have been to in China. It looks like what an airport of a tier-3 city in China would look like if they ever get one.

I pulled out my phone and checked about Georgia’s population: 3.7 million in 2022. This is really small. It’s barely half of Singapore, and almost 1/3 of the city of Nanjing, where both the Engineer and I were born.

Despite its small population size though, what also struck me was the language. The language looks so unique and fascinating. It feels much more like something you would expect to see in Myanmar, or Thailand, or Tamil Nadu, rather than this part of the world. The Professor reminded me that the Georgian language was indeed unique. In terms of linguistic roots, it doesn’t even belong to Indo-European languages, a large language family covering from east to west, from Hindu to Iranian, to Russian, to German, to Celtic, to English. But no, Georgian isn’t related to any of these. The language family that Georgian belongs to, the Kartvelian languages, is basically just Georgian. So, living on the fringes of vast empires, couched in the high mountains, Georgia has preserved a millennia-old cultural tradition like a living fossil.

For the next two days, we spent city-walking Tbilisi, this small country’s capital, with a population similar to the Xuhui District where I live in Shanghai.

Despite graffiti everywhere (many of which cursed Russia) and some crumbling old buildings in the old part of the town, I found the city to be very clean and orderly. One thing I like is that there are many big, sleepy stray dogs everywhere. They were super friendly, and each one of them had a colored registration tag on one of their ears, showcasing some very meticulous regulation at play here. Later, we found stray dogs everywhere in Georgia, even in the mountains. But ALL of them have the ear tags.

In one of the mornings, I joined the Engineer in an early morning jog along the Kura River, which runs through the heart of Tbilisi. The fact that we are able to do that, is a testament to Georgia’s low crime rate. Driving in Georgia is also easy, there is no road rage you see in the US or trespassing of rules common in China.

The food in Georgia is delicious, and I say it as a picky Chinese tourist. Most importantly, it’s also cheap, even cheaper than back home, which is already cheap by American or European standards. With $10 per person, you can already have a great meal. With $5, you are able to get a whole liter of delicious local wine.

The order, safety, and quality of life remind me of one remarkable thing I generally observe about this country: Georgia has a very high ratio of comfort and decency divided by wealth. With a per capita GDP of less than $9,000 (nominal GDP, by IMF), what you got was the experience of a moderately wealthy European state. Its GDP per capita in terms of PPP of more than $25,000 may be a more accurate measure of the actual life there. While nominal GDP is a measurement of a country’s competitiveness when stacked against the almighty US Dollar, the PPP GDP is a closer measure of the actual comfort of residents living there, stripped of monetary shenanigans.

This per capita GDP figure is actually similar to China. But please bear in mind China is a huge country with large wealth gaps across regions. The poorer inland regions pulled down the national average, but the big cities like Shanghai where we live are already on par with developed countries, much higher than Georgia. Still, I feel Georgia has an even higher “comfort & decency per GDP” ratio than Shanghai.

Gori

For the third day, we took a day trip to the small town of Gori, a 1.5-hour drive west of Tbilisi, and the actual birth town of Stalin. I was really curious to witness what kind of place could give birth to such a consequential but controversial man.

On our way to Gori, we saw on the map that there was one section of the highway where it would be probably only a few hundred meters away from the line of actual control between Georgia and Russia-controlled South Ossetia. Will we see border barbwire? Will we see Russian tanks? We stuck our heads out really hard when we drove by that section. But we saw nothing. Nyet. Either the “border” has been quietly accepted by Georgia so there is no need for militarized border control there anymore, or the Russian military is just too preoccupied with their other big war to spare any troops here, or both.

At Gori, we visited the Stalin Museum. We were taken through an exhibition by a local tour guide. Her English was the most monotonous and dullest I have ever heard, to the point I couldn’t even understand half of what she said. She seemed not to be excited by the subject matter either and talked just like what I would imagined a Soviet-era, lifeless party apparatchik would talk. Our own Professor told us way more exciting stories than she did so we followed his “tour” instead.

It’s also obvious that she disliked Stalin, just like (I feel) a great majority of Stalin’s fellow countrymen in Georgia (perhaps apart from Gori residents). I can understand this feeling. It’s like giving birth to some guy, and then he went away to become the head of a big empire only to come back and lord over his hometown with a monstrous instrument of power. It feels betrayed, from the Georgian perspective.

On the way back from Gori to Tbilisi, we visited several monuments. There was the Soviet-era Monument to Saint Nino, a jarring blend of Soviet and Orthodox Christian aesthetics. There was also the towering Chronicles of Georgia, a large structure commemorating the history of this country.

In my mind, I always compare the size of Georgia to a city or even just a county in China. But structures like the Chronicles are constant reminders that this is a nation-state. They have to find money to build this type of thing to tell their own national story. They also need to carve out a budget for military and diplomacy. This is both a burden, as well as an honor, for an independent sovereign state compared with any sub-national entity.

Sudden farewell

The next day, we rented a car to go north, to the mountains. The Professor, the Lawyer, and the Founder formed Group A and had already gone north the previous day. However, just before our Group B checked out at our hotel in Tbilisi, the Engineer got an emergency situation at his company, so urgent that he would have to leave for America on the next available flight, taking his family with him.

This is the type of situation I feared for myself before taking on this trip. Duty calls, and we will all understand. But it’s just sad to see this happening to the Engineer and his family. We sadly parted ways. The Prodigy cried like a river, the only time in the mere 4 days when I saw him really cried. We all held back tears.

So it’s left for us two to drive north.

The mountain, the fortress and the roads

We visited several medieval castles on the way. We also saw a “Russia–Georgia Friendship Monument”, now labeled on the map only as “Gudauri Panorama”. It had a lot of graffiti on it, many of which we suspect to be hate speech against Russia. But the fact it still stood, not torn down, posed as a riddle to us.

Another thing that took us by surprise was that along this tortuous, two-lane mountain road, there were so, so many heavy trucks. There can be only one way those trucks going to and coming from: Russia. We thought the relationship between Georgia and Russia must be cold, because of war and stuff. But the trade route between the two turns out to be super busy. We even had a traffic jam high up in the mountains. It in turn surprised me that despite all of these goods traffic, why the former Soviet masters had never tried to build a railway connecting Georgia with the Russian hinterlands.

We also drove by, big surprise! construction sites by Chinese companies. This may be the first time we saw any Chinese characters. We were not mentally prepared for this.

Our final stop was the resort town of Stepansminda, an Alpine town at the foot of the spectacular Mount Kazbek. We joined forces with Group A and stayed together at a local cottage. On our balconies, we barbecued and drank wine while looking up and appreciating the snow-capped mountaintop not far away, as well as Gergetti Trinity Church, of the Lonely Planet fame. It was the chillest time of the trip, exactly what I was looking for this short break. It’s just a little sad that the Engineer, the Romanticist, and the young Prodigy didn’t share this moment with us together.

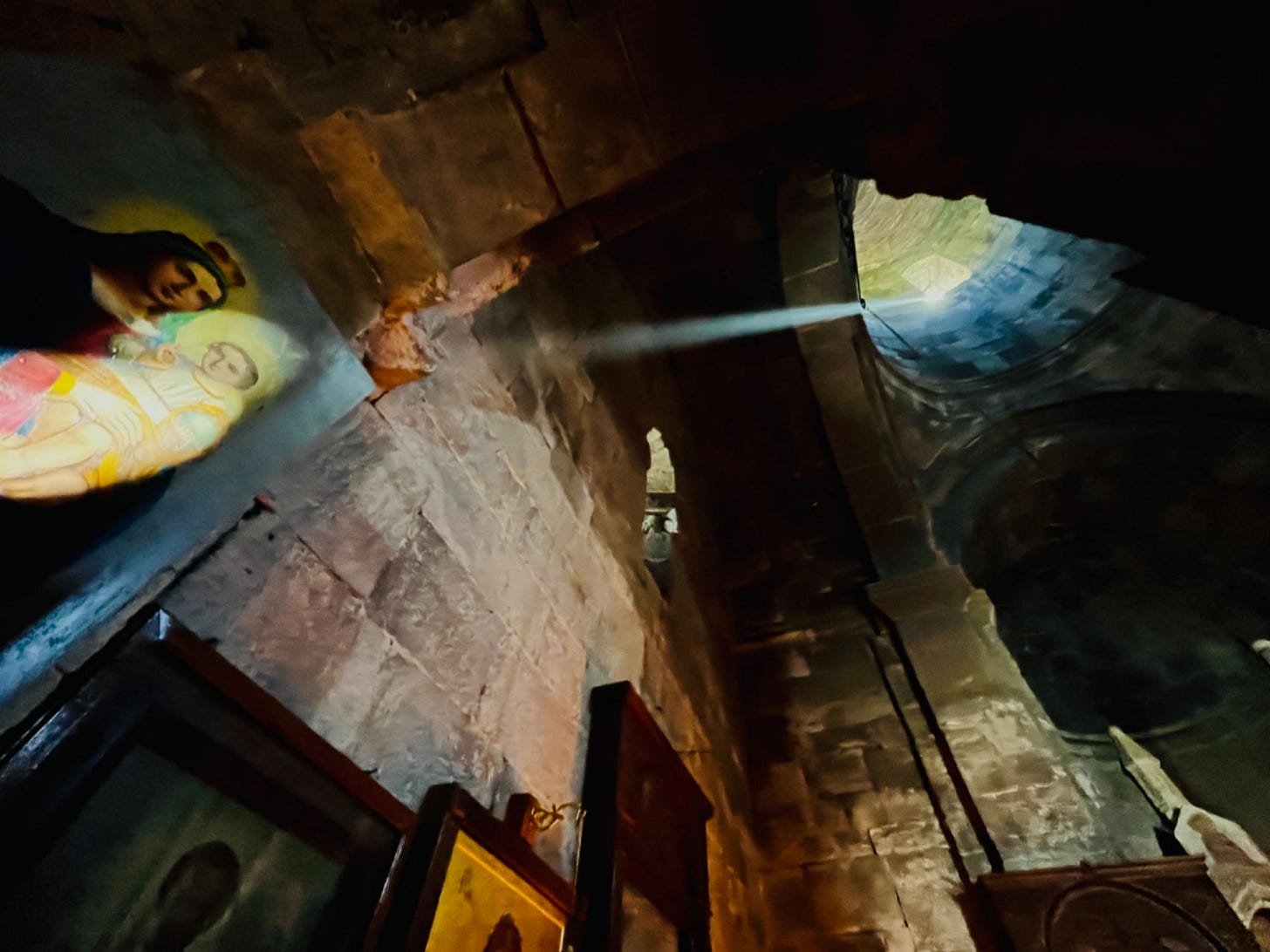

The next day, we trekked to the Gergetti Trinity Church. There, we got lucky. The exact moment we entered the Church, a ray of sunlight touched down exactly on a baby Jesus on the left wall. A minute later, that ray was gone elsewhere.

We then had some lunch and decided to head to a much wilder tourist spot, the Zakagori Fortress.

There are no good roads to Zakagori, only 20 kilometers of bumpy, 1-lane mountain tracks. At times we even had to drive our SUVs through streams, or narrow bridges built by barely more than 4 water pipes. It’s a little scary, but quite thrilling.

Halfway through it, we lost Group A. There was also no cell phone signal. So my partner and I stopped at a river and waited. We waited for half an hour and took some pictures. Some cars appeared in the distance, but none of them the Cherokee driven by Group A. Since it’s only a one-lane road we had just traveled from, we judged Group A must have somehow turned back for some reason.

Faced with the choice, my partner and I, ever two adventurers, decided to charge ahead. After 2 more hours of an excruciating ride, without any cell phone signal, and with several difficult meetups with vehicles coming from opposite direction and the anxiety that our car could break down at any moment, we finally arrived at a monastery only 1 kilometer away from Zakagori.

It was like this otherworldly, idyllic place. 世外桃源. There, a young lady served us some juices and cookies, while the sign at the counter read “pay as you want”. I pulled out all of the Georgian Lari coins in my pocket (I hate coins) and asked if it was enough. She smiled and said fine. So decent.

In the backyard, some nuns were marinating 2 pig heads. Ducks quacked and chickens ran around.

We also finally had wifi and knew that Group A turned back because of fuel shortage. We said “goodbye” to them again and charged ahead to the last leg of this adventure.

After 10 more minutes of road bumps, we finally arrived at Zakagori, a deserted, half-destroyed 1,000-year-old ancient fortress on the top of a hill, looking across a confluence of rivers, and staring down at the direction of Russia. We climbed that hill, and posed at the road sign that forbade us to go further into this border area. There was only one more couple, looking French, who were at the Fortress at the time. We were glad to make it.

At the foot of that hill, there was a block of rocks, held together by wires. It looked like the walls of a modern army barrack. The new Zakagori “Fortress”. There was a Georgian flag, but nobody seemed to be there.

On the final day, we drove back from Stepansminda to Tbilisi. This is an almost 4-hour ride, even though on paper it’s only ~150 kilometers apart. The reason it takes so long is because it’s very mountainous, and as I have just explained, there is large traffic of heavy trucks to and from Russia.

On the way back, I realized there were actually two Chinese construction sites, not just one. They seemed to be drilling holes into the mountains.

I had a hunch. Were they building on the same thing? I was right. I did some research and figured out that what they were building was the 8,800-meter-long Gudauri Tunnel. And it just dawned on me, the next time when I will be here if I ever come back, the mountain road section we just spent 2 hours driving may be shortened to a mere 10 minutes.

The belt & road?

This makes me amazed and incredibly proud.

For the second part, possibly to be out next week, I will deal with the more serious topic. Stay subscribed and stay tuned.

Follow-up note: Part 2 is here.

I was speaking to a Georgian waiter at a Ukrainian restaurant here in San Diego, CA and asked him why he left Georgia. He remarked it was because of the old Soviet-style corruption which makes it difficult to get ahead on merit alone. You mentioned the wealth disparity and hope you will discuss corruption in your next part. It seems exotic and I like your “living fossil” description.

Excellent travelogue, I really enjoyed the read and how you have interwoven the personal, subjective recounting of the trip with historical facts and geopolitical analysis. You should travel more. :)