Thank you for the strong support for Part 1 of China’s schizophrenia, which quickly became my 2nd most popular post to date. This is Part 1 in a one-sentence nutshell: I explored a “vocal minority vs silent majority” model to understand many conundrums about today’s China.

In Part 2, I will use the same framework to do something even more interesting: making predictions. But before I start, let me recount a bit about my Chinese New Year/Spring Festival holiday.

For the past few days, I first visited Hangzhou to join my grandma and cousin for CNY dinner and then went down with my parents and wife to Guangzhou, Foshan, and Shunde for warm weather, and, food!!! Guangdong cuisine is one of my favorites, ranking before Italian and Japanese. Yes, you hear me correctly, on Robert Wu’s global food ranking list, there is no such thing called “Chinese food”. It is ridiculous to group Sichuan hotpot and Cantonese roasted goose, and to group flour-based wide noodles of Xi’an and rice-based cakes of Zhejiang, under the same category.

Another highlight of the trip was the visit to the Whampoa Military Academy. It’s the place I had always wanted to visit, which is a little schoolyard where almost the entire history of China’s 20th century was packed into. (For details and photos, please check my substack chat sent to subscribers.)

In the middle of my trip, I broke off the pack temporarily to catch a high-speed rail for a day trip to Changsha, the capital of Hunan Province (2.5 hours each way) to attend a local business conference. Later I managed to return to Guangzhou within 24 hours for the Valentine's dinner with my wife.

Let’s pause a little bit to appreciate what I am saying here. This is a 670km (~410 miles) train ride through the Nanling Mountains, the mountain range that separates China’s Yangtze River Valley area from Pearl River Basin, the tropical from the sub-tropical. I checked on Google Maps that in terms of distance, my trip is almost the exact equivalent of traveling from San Francisco to Las Vegas to attend a 4-hour conference, through a tunnel system under the Yosemite, and coming back to SF, in one day. I just sometimes have to marvel at the huge transformation that the high-speed railway system has done to the Chinese way of life.

So why did I take this business day trip in the middle of the holiday? Why on earth there was even a business conference during CNY??

It turns out that local governments these days are very hard-working and never waste a chance to promote business and investment. A growing trend for inland cities to attract investment nowadays is to target investors and entrepreneurs who were born and raised there but migrated to higher-tier cities. I don’t know if this is a big thing in the West but Chinese people generally have this “strong attachment to roots and hometown乡土情结”. So this strategy makes sense, simply because those “returnee businesspeople” are not only familiar with local life but are also more willing to contribute to local development. (Probably not in the West, otherwise South Africa should be able to lure Elon Musk to set up a new gigafactory there.)

So what is the best occasion for gathering a lot of “returnee businesspeople” in one stroke? Spring Festival, of course, when many people returned to their hometowns. So instead of relaxing, these government officials and civil servants worked their tails off starting from Day 2 of the holiday to prepare for the 300-people conference held on Day 5. This is the equivalent of your local city council working tirelessly to host an investment symposium in the middle of Thanksgiving or Christmas holidays. (Day 5 of CNY is also the traditional day to welcome the “God of Wealth”. So the metaphor here is hard to miss: for local governments, those businesspeople are their gods of wealth.)

For my own part, I am only remotely related to Changsha or the Hunan province (my mother was born in Hunan but she left there when she was only 8), and I have never set foot in Hunan until last year. I will explain in later paragraphs why I got invited and took this “business break” out of my real break.

The Future

As I said in Part 1, although understanding the past is important, what’s more important is how we progress from here. Our decisions will only be based on what we expect to happen, not on what has happened.

So, how should we expect the “Duo-China” model to change in the years to come? More precisely, of the “Liberalist China” and “Traditionalist China”, which one will get bigger and stronger in relative terms? This is a crucial question that anybody who has a stake in China’s development should pay attention to, simply because the “Duo-China” model is so fundamental to the decisions and choices of the Chinese government.

Here are two important disclaimers before I give you my answer. Firstly, notice that I try to avoid the words “liberal” and “traditional”, but instead opt for heavy-sounding words like “liberalist” and “traditionalist”. I deliberately made these choices to avoid unintended cultural connotations. By “liberalist”, I do not mean “liberal” as understood by contemporary American culture as a “left-wing liberal”, nor do I mean someone who necessarily think the current western system is to be entirely copied to China. What I mean by “liberalist” resembles more the classical, John Locke/Adam Smith-era liberal. A core aspect of my liberalist is the belief that individual rights and freedom are at least as important as the collective interest, if not more important. For liberalists, rules, laws and governments exist to regulate activities between free individuals.

By “traditionalist” I do not mean people who strictly adhere to ancient Chinese lifestyles, but someone of a specific income and education profile and a specific paternalistic culture. Likewise, the key to being a “traditionalist” is to believe collective interests normally precede those of an individual. Individuals exist as subordinates to authorities, and authorities are to be respected, but also to be counted upon to provide protection.

The second disclaimer is that when I talk about “the future”, I am not talking about the next year or so. The right timescale should be at least 5-10 years out, even a few decades out, which is the only scale that fits a discussion of structural movements at such a deep level.

Now, here is my answer: In the foreseeable future, liberalists will get larger in number than they are right now, even though they will still be outnumbered by traditionalists.

I also believe, contrary to what many China doomsayers are saying (such as Noah Smith), China’s government, overall, will also want the “Liberalist China” to grow stronger.

And here is the thing, I am not talking about blind faith here. I am talking about something that’s only the necessary outcome of the set of realities that we are dealing with today.

What’s the biggest reality of China today? As I explained in Part 2 of my Noah Smith critique, the biggest reality is that the golden era of China’s property development, a.k.a urbanization, is over. Nobody has illusions about that. The violent delights of the last 3 decades have met their violent ends, leaving behind a gaping hole that demands to be refilled.

Out of this basic reality is the new consensus: China must, ASAP, climb up the global value chain. An analogy I often like to use is that, to replace the single biggest pillar of the Chinese economy which used to be real estate, China would have to find for itself the GDP equivalents of at least Germany (auto and high-end equipment) + Saudi Arabia (new energy) + South Korea (chipmaking and shipbuilding).

This new consensus will bring about strong forces to change our society from at least two important directions: 1) the financial system and 2) the population mix.

#1 Financial system

Property should never be simply understood as a piece of land or some space for people to live or work. Property is a key financial instrument. Indeed, it has been the most important financial instrument in China for many decades.

At the very least, property serves as the best collateral to help build more leverage into the system. The government, the real estate developers, and eventually the households - every single player in the property market - get bank financing by pledging their property.

The corollary of a dominant property sector is the dominance of the banking system in China’s financial system. Likewise, a waning property sector will mean a perennial drag on the banking system, eventually making the banking system unable to function as robustly as desired. As a result, local governments are losing a big chunk of financing to pay bills, corporations are unable to fund expansion, and household consumption is tied down.

Therefore, what China loses with an imploding property market is not just a major limb of our GDP, but a whole system of arteries and veins that pump vital energy to every cell of the economic system.

Of course, a weakened banking system can’t be counted on to support the “high-tech” sectors of the future. And let’s be honest, even if China’s banking sector remains as strong as before, it will not be counted on to play the main role in supporting high-tech sectors. This is because the core ingredients of “high-tech” are technology, know-how, intellectual property rights, human talent, skills, and data. All of these are intangible assets that regulated intermediaries such as banks will find difficult to evaluate and perform risk management on. So it’s no surprise that most of China’s top innovative companies of the past 2 decades (Tencent, Alibaba, BYD, Bytedance, etc.) did not ow their successes to bank financing, but to foreign venture capital.

So instead of the banking system, and with foreign venture capital plummeting, the domestic capital market has to step in, changing from an auxiliary financing venue to hopefully become the main source of financing.

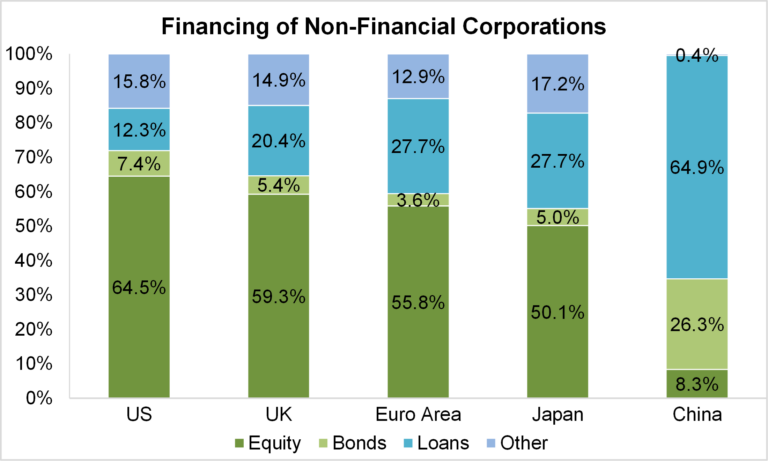

Just look at the chart below. According to SIFMA’s 2023 Capital Markets Fact Book, in the US, “capital markets fuel the economy, providing 71.9% of equity and debt financing for non-financial corporations.” In China, however, the situation is the exact opposite. It is bank financing which accounts for as much as 64.9%.

But I believe, due to the above-discussed new constraints and new aspirations, a gigantic structural shift will have to take place here, making China look more and more like the advanced economies on the left in terms of financing structure.

This is because, while the banking system is anchored in property, the capital market is anchored in market participants’ minds. As long as investors believe in the growth and quality of those high-tech companies, there will be a market for those companies to raise funds on the capital market, with no worries about how many “hard assets” such as land those companies can pledge as collateral. A thriving capital market will also be a boost for the public as well as household finances, lessening the over-dependence on property assets.

Within this broader context, the unprecedented string of capital market-friendly events of recent days will start to make sense. These events, which I have all alerted you before, include:

Requiring SOE to incorporate investor-friendly metrics into KPI measurement, effectively grading socialist managers on (at least partially) how well their capitalist shareholders are treated.

Unprecedented nice words to place investor interests over issuer/corporate interests, such as “Only when investors are well protected, will there be a solid foundation for a prosperous market”, “Build an investor-centric capital market建设以投资者为本的资本市场”.

Local governments specifically pay visits to listed companies within their jurisdictions to address their concerns (linked article in Chinese).

Wu Qing’s appointment as head of CSRC. First-ever securities regulator who actually has a securities background, rather than a banking background like all of his predecessors. Mr. Wu can be seen as the personified symbol of the ground shift from banking to the capital market.

Immediately after Wu Qing took office, CSRC issued massive fines for securities fraud and market manipulation right on the eve of Chinese New Year (government employees worked overtime again). Making big monetary penalties, a practice long used by the US SEC has only recently taken off in China.

Are these events mere gestures? I don’t think so. Once you put them in the right context, you will start to see they are quite consistent: Since the over-arching goal for the future is to make the capital market a main financing channel, then investor protection should be put on the top of the agenda. After all, a strong capital market is not possible if investors can’t make money. These policies are just the beginning of a long string of policies designed for the long-term health of the capital market. They can’t be simply written off as empty talk.

So why will a more dominant capital market make “Liberalist China” stronger? Because the capital market is the main hallmark of liberalists. As I wrote in Part 1, a key feature of the liberalists is that most of them hold a stock trading account. Holding a financial stake in the capital market helps people to think in a certain way. For instance, they tend to value concepts such as transparency, trust, fiduciary duties, and contractual obligations more than non-investors. They also tend to ask more questions and demand more answers, as their fortunes fluctuate in real time to the ebb and flow of economic sentiment.

A stronger capital market will also make the government deal with things a little differently.

Unlike the banking sector, which is a form of indirect financing that can be centrally micro-managed, the capital market is the market economy in its most sophisticated form. Many people haven’t realized it, but the capital market in China also functions as a gigantic, real-time voting machine, where all market participants get to “vote” on a real-time basis through buying and selling. It’s the most effective and publicized gauge of public sentiment that’s rare to find in China.

Recently, we have been offered a great example to illustrate my point: the video game regulation blowup that I did a detailed analysis on. Had not the video game sector been tradable on the stock market, and had not hundreds of billions of value been wiped out in an instant, the game regulators would not have realized the big mistake they had committed, or how fragile market sentiment really was. After all, China has a tightly controlled media space so you don’t really have a good tool to gauge sentiment. But money doesn’t lie. A crash in the market is more powerful than a million words.

Obviously, managing well this market requires a completely new set of skills than what the Chinese government is used to. It takes a high level of professionalism, coordination, empathy, patience, and confidence to be able to deal with something as mercurial as the capital market. You can’t just respond to problems by shutting things down or hiding away from the problems.

Going from a banking/property-driven economy to a capital market-driven economy is analogous to going from an agricultural, land-based society to a seaborne, trade-based economy. Many rules will be rewritten. Value systems will be upgraded.

And I think we are seeing early signs of this maturation. Last year, the National Bureau of Statistics stopped, for a while, to publish controversial youth unemployment data. Half a year later, they republished them in an improved format. “Half a year” is definitely too long than desired or necessary. But again, we are at an early stage of this.

#2 Population mix

Population mix change is another pathway to bring about more liberalists.

A key observation here is that the more wealthy, the more urbanized, and the more educated people are, the more likely they will be liberalists.

Many people believe China has already become quite wealthy. Yet this flawed judgment is clouded by two facts: 1) Yes, the absolute number of high-income Chinese are as large as the entire population of any Western country, so their presence is hard to miss, and 2) as I explained last time, liberalists are far louder.

In reality, though, the country is much poorer than we are led to believe, with 80-90% of the population living below the typical “middle-class” standard. I need to stress again here: the median income for this country is only $4600 per year, and“median” means half of the population earns less than $4600.

What do you expect someone who earns $4600 per year or less to understand about concepts such as contracts, rights, social trust, and good governance? More likely their minds are numbed by the daily grind and/or free TikToks. More likely their educational level will not even allow them to articulate themselves coherently.

But here is the thing: Precisely because we are still “poor”, China’s economic growth on a per capita basis is far from over. Despite short-term setbacks, more people will continue to join the middle class.

This trend will come in both directions: what the government wants and what the people want. What the people want is easy to understand: we want a better life. What the government wants is the transformation into a high-tech, high-value economy. But that economy will require more engineers, scientists, product managers, creators, entrepreneurs, and generally high-skilled workers of all kinds. It would be ridiculous to assume China’s middle class will only dwindle when China tries to “value up”.

Parallel to this growth, urbanization is bound to continue.

Urbanization in China is far from over. The real urbanization rate is far below what headlines suggest. I am so lucky that

, one of my favorite China-based substackers, has just written a fascinating X thread precisely on this topic (a must-read!) His main point is that China’s headline urbanization rate of “66%” far overestimates the real urbanization level, as it includes huge areas of “low-level urbanization” that any sane person will not treat as “urban”. For example, here is the photo David took somewhere in the Hubei Province. It is categorized as “urban”, but judge for yourself if it is:So what will happen in the next decades? Very simple. As income rises, people in rural and those low-level urban areas will keep migrating to high-level urban areas. In that way, a new round of urbanization will continue.

[By the way, David wrote

substack but doesn’t update as frequently as he did on X. Please subscribe to his substack and urge him to write more here!]Now it’s time for me to circle back to my Hunan day trip.

Why did I get invited? Because last year, I moved the headquarters of my firm, BigOne Lab to Hunan, the ancestral province of my mother. Besides local fundraising opportunities and generous subsidies, the best thing about Changsha (capital of Hunan) is that I can pay someone half of the cost of what I pay in Shanghai. And here is the beautiful part: this someone enjoys a much higher standard of living than s/he does in Shanghai with half of the pay.

This is Changsha by the way:

On average, a worker in Changsha can buy housing with 6 years of salary, a ratio that’s unimaginably low among China’s 2nd+ tier cities now. Many of the people we hire in Changsha spent a few years in first-tier cities like Shanghai and Shenzhen, accumulated some skills but decided to return to somewhere closer to their hometown due to the high cost of living in the first tier. In the end, though, their hometowns will start to catch up to first-tier cities’ development levels, on the back of tens of millions of those individual choices.

And Changsha is not a unique case. Inland cities like Hefei, Chengdu, Chongqing, Wuhan, Hefei, and Xi’an as well as surrounding cities in Yangtze River and Pearl River deltas will continue to attract more people to move in. Urbanization will continue and per capita income will rise, for the very simple reason of the still stark differential between where we are now and where we aspire to be.

So eventually, my discussion of whether “Liberalist China” will keep growing comes down to the multi-trillion-dollar question of whether China’s economy will keep growing.

And here lies my ultimate challenge to the “Peak China” narrative (which I will probably expand on in the future): It is not about some metaphysical pseudo-discussion of whether China’s political system works, or whether Xi is a smart or a dumb guy.

My reasoning is as simple and as down-to-earth as this: if the majority of the people still have many unfulfilled aspirations and are still hard-working (even our government employees work during holidays), there is no way for this country to have peaked.

It’s simply nuts to think Chinese people will just be content with a median income of just $4600.