As briefly mentioned in last week’s Briefing #66, something interesting has been happening in China’s online discourse recently. China’s censorship machine, assumed by many to move in only one ideological direction, has started to bite from both ends of the political spectrum.

On the far left, a movie review of Youth (芳华) - a fairly unremarkable 2017 film about a military performance troupe set in the 1970s and 1980s - suddenly went viral on domestic video platform Bilibili, at least for a few days.

Youth was never meant to be a grand historical statement. It’s the kind of movie you watch once, feel a vague sense of nostalgia, and then move on. This time, however, the film was taken out of the grave and radically reinterpreted. A popular Bilibili reviewer reframed it as a hidden ode to the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

Not a tragedy. Not a warning. An ode.

The claim itself is almost comical. I won’t waste your time by going into details of this movie. But what I can tell is that, if anything, the movie can only be described as something to criticize and reflect on that era. Moreover, both Feng Xiaogang, the director, and Yan Geling, the author of the original novel, are commonly known as harsh critics of the Cultural Revolution.

So this claim is about as credible as arguing that The Godfather or Zootopia is secretly praising the Cultural Revolution. In fact, under the same logic, any story reflecting some elements of class difference, injustice, or social stratification can be reverse-engineered into Maoist revolutionary nostalgia.

And yet, the video worked.

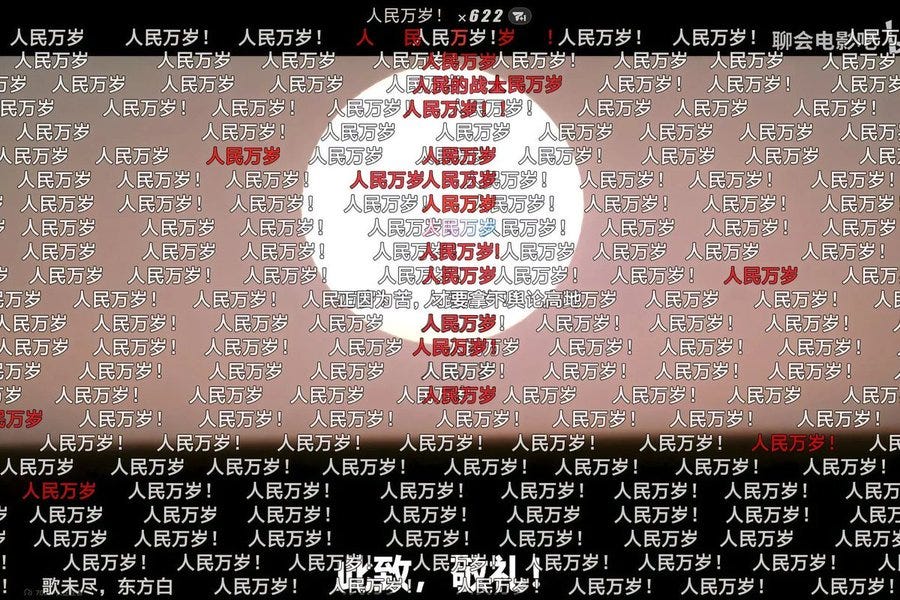

Partly because the influencer is genuinely good at storytelling, the review racked up tens of millions of views in just a few days before it was eventually taken down. On Bilibili, viewers can send so-called “bullet chats”—comments that fly across the screen as others watch the same segment. I was told this video accumulated more than 300,000 bullet chats, enough to completely drown out the actual film if you turned them on.

Many of those bullet chats repeated the same slogan: “Long live the people.”

In this worldview, the Cultural Revolution was a righteous uprising of the proletariat smashing entrenched elites. Mao was a misunderstood hero, smeared by later narratives, whose true intentions are now being rediscovered by a new generation.

This interpretation sits in direct conflict with the official Chinese position, which describes the Cultural Revolution as a catastrophic mistake—an “apocalypse” that destroyed institutions, cultural heritage, and lives. This contradiction alone made the video politically radioactive.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, another ideology, once fringe, is moving closer to the mainstream. It is often referred to as 皇汉, or Han ethnonationalism.